For almost half a century, David Wright has been producing glass with religious themes for sacred spaces in Australia, including sets of windows for over thirteen churches and fifteen chapels in schools or hospitals. He was born in Melbourne in 1948 and grew up with a background in the Anglican Church. He would eventually marry Sue, an Anglican priest. Most of his religious work is in Anglican churches and chapels.

For almost half a century, David Wright has been producing glass with religious themes for sacred spaces in Australia, including sets of windows for over thirteen churches and fifteen chapels in schools or hospitals. He was born in Melbourne in 1948 and grew up with a background in the Anglican Church. He would eventually marry Sue, an Anglican priest. Most of his religious work is in Anglican churches and chapels.

As a boy, he also spent time with his grandparents in Flinders at the southern end of the Mornington Peninsula where he absorbed the imagery of the Australian coast. Later his painting trips to the Australian desert developed his awareness of the colours and forms of the Australian landscape. Flinders has remained an important place in his life.

Wright had an artistic bent from an early age and was influenced by artists such as John Brack while still at school. He earned an architecture degree in the early 1970s and has taught and lectured throughout Australia. His commissions include windows for Parliament House in Canberra and 22 windows for Temple Beth Israel Synagogue in Melbourne.

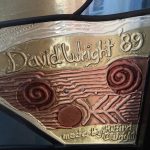

Wright developed his own special technique of melting the glass in the kiln, fusing different layers of colour and applying metallic lustres to the surfaces; by using an assortment of textured moulds, he also embedded patterns into the glass. This method of slumped glass, combined with sandblasting sections and other treatments, creates his unique look that catches the light and provides rich colouring.

St James Church, Sydney

In the late 1980s, Wright produced a vast 90 square metres of glass to enclose three sides of the new Chapel of the Holy Spirit in St James’ Church in the centre of Sydney. The church was designed by convict architect Francis Greenway and dedicated in 1824; it forms part of the historical precinct of Macquarie Street. The magnificent Creation window was a bicentenary project.

Centre panel and right side.

In the window, the work of God’s creation is expressed by the Holy Spirit swirling in wind and air, fire and water. Across the centre, we have an Australian landscape embracing the heavens and the earth, all caught up in the dynamic circles of the Spirit’s action. The Australian bushfires and floods become powerful symbols: the fire of creation on the left hand side flings the planets into their orbit; the streams of water on the right hand side evoke the living water flowing in the desert and the rebirth of baptism. Throughout the window, the motifs in the slumped glass suggest fossils embedded in the rock, and embryonic life forms bubbling forth into existence.

In the centre, the earth pushes up a great tree, the Tree of Knowledge from Genesis and the Tree of the Cross from the Gospels, representing the original creation and our re-creation in Jesus’ death and resurrection. At the centre is the spiral mandala of the mystery of God. Surrounded by small crosses and the crown of thorns, it is Christ at the centre of all creation. This focal point generates the entire composition of the windows. Here the spirit of Christ ascends to the heavens while, on earth, Pentecost power descends to touch the disciples with the flames of the Spirit.

Catholic Chapel at Cabrini Hospital, Malvern Melbourne

The centrepiece of David Wright’s 1994 suite of seven windows at Cabrini Malvern is a magnificent panel depicting the Crucifixion, Resurrection, and Life Everlasting (Left).

The Institute of the Missionary Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus was founded in 1880 by Francis Cabrini to support impoverished Italian immigrants in the USA; the sisters came to Australia in 1948. Wright describes the Cabrini project well: The sisters of Cabrini are a Catholic order and they stand very much for both sides of life: cleverness and creativity. Looking at their mission statement, they are very strong about the cleverness of the care, with up to date technology, but this is always balanced by the spiritual side, in all senses of the word, from the welcoming, the comfort, the handholding, the friendship right through to the giving of the sacraments and looking after peoples’ spiritual needs in total… As I was walking through the [chapel] space thinking of these two sides of life, the spiritual and the clever, I thought the windows in the chapel should express this. Three windows on one side express the spiritual journey; the three windows on the other side are about the health care. The central window expresses the relationship between the two (Interview, Ausglass, Summer 1994/1995, pp. 17-18).

The central Christ window speaks of the changing seasons and the cycle of pain and rebirth (seeds sprout in the brown earth). The diagonal and the circle make this a very dynamic composition. The figure of Christ rises from the earth, affixed to a cross which is barely visible in the midst of an Australian forest of gum trees. The eternal circle of life which surrounds him is marked out with gum leaves in their characteristic flat green and purple. Above him, new life flourishes in cascading leaves and fruit, while the Holy Spirit, in the form of clear circles and red triangular flames, breaks into the circle from the deep blue infinity of the heavens. The rainbow affirms God’s promise of fidelity. The Spirit flames flicker about the figure of the crucified Christ, now glorified with a halo as he rises in the new life of resurrection. In the hospital context, it is an eloquent reminder that, in Christ, it is possible to transcend the limits of the human flesh and conquer the bonds of death.

The spiritual journey of love and nurture, represented on one side of the chapel, begins with a boat arriving across the waves onto a verdant shore of flowering trees. The boat, guided by the Holy Spirit (again the white circles and red flames), carries two figures: the Virgin Mary who cradles the Christ child. There is also a clear reference here to Mother Cabrini, missionary and patron saint of immigrants.

The spiritual journey of love and nurture, represented on one side of the chapel, begins with a boat arriving across the waves onto a verdant shore of flowering trees. The boat, guided by the Holy Spirit (again the white circles and red flames), carries two figures: the Virgin Mary who cradles the Christ child. There is also a clear reference here to Mother Cabrini, missionary and patron saint of immigrants.

The second window, which repeats the circular form of a mandala, refers to the Eucharist and incorporates the symbols of the loaves and fish. Centred on the figure of Christ, the circle of the family of the Church embraces the sea and the sky, against the background of the Australian forest. The whole is encompassed by the circular symbols of the Holy Spirit and is set under the rainbow arch of God’s loving fidelity.

The third window, said Wright, is about prayer and about finding a way through (Interview, p. 19). After arriving on shore, the boat is left in the waves. Led by the Spirit, the person pushes through the verdant forest to transcend earthly life. The flames of the Spirit set the forest gums on fire – the bushfire being a symbol of regeneration. Death gives way to newness of life.

The other side of the chapel represents the ‘cleverness’ of Cabrini health care. The first window shows birth, the beginning of life. The human person, umbilical cord attached, is drawn by caring hands into the river of life. At the top and bottom, seeds sprout – they will become the forest of life. This miracle occurs under the watchful eye of technology, the theatre lights shown at the top of the window.

The second window on this side again combines images of technology of the left, with the earthly forest at the top, and the presence of the Spirit on the right. Around the patient, we see the anaesthetist, the surgeon and the nursing team to the left, with, on the right, the pastoral care team holding the patient’s hand and anointing with holy oil. As a symbol of selfless service, two figures at the bottom wash the patient’s feet.

The final panel speaks of death. At the end of life, the person reaches a threshold: the earthly forest is left behind and the river of life runs into the eternal sea. The hands of loving care let go, and the person moves beyond into the golden promise of the next life.

The Magdalene Window, St Peter’s Cathedral, Adelaide

In 2001, David Wright completed a monumental window for Adelaide’s Anglican Cathedral. The subject of this window is the resurrection of Jesus Christ on Easter morn. It shows the moment when Mary Magdalene and the women arrive to anoint Christ’s body at the tomb. Thus it celebrates the role of women in the history of the Church and in bringing about social change in Australia today. It is a celebration of the fact that, since 1992, women have been ordained to the priesthood in the Anglican Church of Australia. The window fills the southern transept.

The blue circle at the centre of the window is the tomb of Christ where two angels unfurl the shroud of Jesus in a dramatic spiral (at the bottom left of the shroud, is a needle, symbol of the unseen work of women through the ages). Three women in colourful patterned dresses surround the tomb, their hands reaching out to one another in a supportive dance of life. The one at the bottom carries the jar filled with the aromatic herbs they intend to use to minister to the body of Christ. The figure on the right is Mary Magdalene, the intersecting lines form a mitre on her head; at her feet lies a crosier; she holds a blood red egg, a reference to a legend proving the resurrection of Christ.

The tomb is surrounded by the circle of the earth, filled with sprouting plants and flowers. This fertile symbol of growth and regeneration turns the tomb of the dead into the womb of new life. The whole earth is surrounded by the triangular flames of the Holy Spirit.

When the women arrive, the tomb, of course, is empty. This is beautifully represented by a great spiral which leaves the tomb over Mary Magdalene’s head and spirals through the upper lights, becoming the rainbow of promise, to return on the left hand side to the golden disk of the risen Lord, hidden in the garden. His outstretched arms close the circle of the women’s dance. The resurrection of Christ gives life to all.

Finally the earth and the event of the resurrection are placed into a cosmic context. The spinning earth is surrounded by the sun and moon, stars and planets. The grand beauty of the universe evokes the eternal care and providence of the Creator God and the nurturing ministry of women encourages all of humanity to care for the earth, our common home.

These three major examples of David Wright’s religious windows illustrate his technique of slumped glass; they help us to ‘read’ his symbolism, to appreciate the geometry of his construction, and to enter into the religious dynamism of his concepts. It is extraordinary that he is always able to reference the Australian landscape to anchor his lofty ideas in the here and now.

TOM ELICH chairs the National Liturgical Architecture and Art Council and is director of Liturgy Brisbane.

References:

Peter French, “A New Conceptualisation of Australian Religious Iconography: the Case of David Wright”, Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration and Convergence, Proceedings of the 32nd International Congress of the History of Art (Melbourne, 2009) pp. 405-409.

Peter French, The Life, Art and Religious Iconography of David Wright (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015).

Gerie Hermans, “To be Clever and Creative… the Heart of Glass is in the Making… An Interview with David Wright”, Ausglass, Summer 1994/1995, pp. 14-19.

Anonymous, St Peter’s Cathedral brochure, “The Magdalene Window”, nd.

Anonymous, St James Church brochure, “The Chapel of the Holy Spirit”, nd.

Images

Cabrini Hospital Chapel: courtesy of Cabrini Health – Strategy and Marketing, with the generous help of Damian Coleridge.

St James’ Church, Sydney, and St Peter’s Cathedral, Adelaide, by Tom Elich.