The Power of Touch

The Power of Touch

Born in Melbourne, Philip has studied extensively in Theology and Fine Art. He holds several Post Graduate degrees culminating in his PhD exhibition in Sculpture and Drawing at Monash University, 2015. During 30 years of art-making he has been presented in a range of solo and group exhibitions, nationally and internationally. Philip continues lecturing in Drawing and Sculpture at tertiary Art Schools in Melbourne. His studio is based in Woodend, Victoria, where he lives with his wife and children.

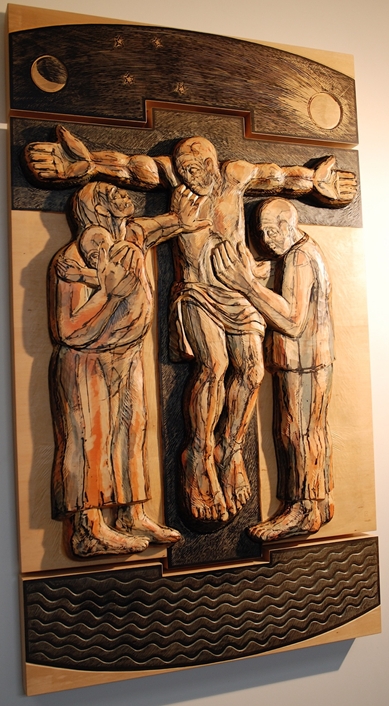

I have enjoyed the privilege of being involved in major art commissions, including St Patrick’s Cathedral at Parramatta, working under the architect Aldo Giurgola. This project was The Stations of the Cross, installed in 2003.

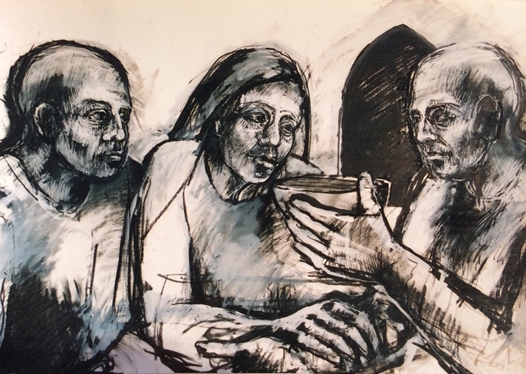

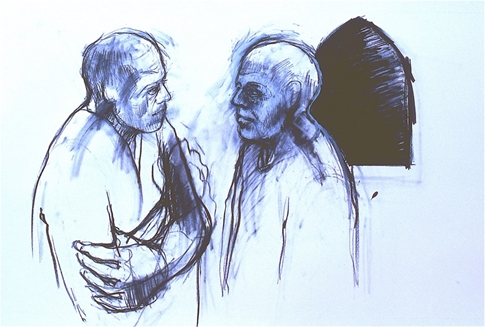

The subjects of the Stations are derived from the scriptural narrative of the Synoptic and Johannine Gospels running from the Last Supper through to the Resurrection. As with all my work, the imagery concentrates on the place of human touch within the drama of life. My source of inspiration came from the very simple and expressive phrase of Veronica Brady, To love is to be vulnerable. My exploration of the Paschal narrative emerged through a constant layering of mark making from the initial figure drawings on paper to the resolved carved wood polychrome panels. The scale of the figures is approximate life-size. Viewed at eye level, they are accessible to touch in an attempt to explore the possibility of intimacy both within the image and between the sculpture and the viewer.

Between the carved images are placed the text panels drawn from the suffering servant narrative in second Isaiah 53-55, which echoes and prefigures the the Passion narrative. Relating to the imagery via association rather than prescription, the text provides another layer of interpretation to the Paschal narrative. The words articulate an account of one person’s love which leads him to humiliation and suffering on behalf of the wider community. The language and poetry are remarkably contemporary in light of global events of human suffering and struggle, seen from Middle Eastern and Afghanistan tragedies to local bushfires and the ongoing refugee crisis. The Stations of the Cross also try to acknowledge the history of suffering at Parramatta, the site of one of Australia’s early prisons and its penal executions.

I wanted to depict Christ with both a vulnerability and also an acceptance of himself and his journey. The Christ figure is bald, exposed, to try to focus on each moment as the place of contact with the other and with the inner self. This ‘poverty of spirit’ opens him to a great sense of compassion with those who meet him on the way. For the most part, the narrative is conveyed in the gestures expressed through the face and hands. To acknowledge the scriptural account is one thing, but it is also important to make a connection with and beyond the richness and ordinariness of the human experience.

The Stations visualise layers of intimacy and abandonment in the account of Jesus’ life, death and resurrection, with the hope and fear that accompanies them. In retelling the story, the imagery opens up something of the presence of Christ. I am trying to do what the American theologian David Tracy spoke of when he said of Jesus that he engages peoples’ imaginations so that they could be more deeply in touch with their own experience. As Tracy explains, Jesus interactions with others challenges them to redescribe our human reality in such disclosive terms that we return to the ‘everyday’ reorientated to life’s possibilities (Blessed Rage for Order, 1975, p. 207).

My imagery as a whole is playing with the familiar and the unfamiliar in attempting to make a place of such encounter. Consequently, in some of the scenes less is shown than what would be required to identify the image as part of the narrative. In other scenes it might appear that more is shown than could be identified in the Gospel narrative. Each of the images is an invitation to those in front of the work to interpret what grows from the story, the times, and the place.

The themes explored in The Stations of the Cross at Parramatta are re-echoed across the range of my commissioned and non-commissioned works.

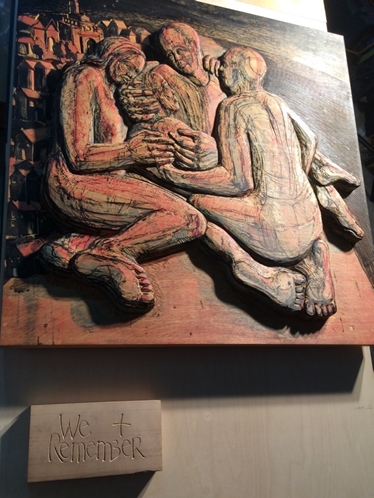

We Remember looks again at Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ to form a memorial to the homeless who have died within the inner suburban parish community at St Kilda, Melbourne. We encounter this kind of imagery on a daily basis: figures carrying the bodies of their loved ones in the ongoing refugee crises, the battlefields of Black Lives Matter, the masked health workers caring for and carrying those who have died during the global pandemic.

There is something in feeling the weight of another that grounds us in the moment: connection and loss, intimacy felt and fleeting. Bearing the weight of the other is tangible. Yet this memorial sculpture attempts to grasp what is perhaps not always so tangible, completely other and yet completely present, somewhere between ‘the sacred and the bleeding ordinary’.

We Remember provides a physical place within the parish church to carry the weight of the profound connection and loss experienced as the community remembers those whom they carry. The memorial offers a place for those who have experienced no place. It offers the opportunity to touch the memory and be touched by it. Symbolic of these encounters, skin touches skin and hands focus our attention on where contact is made. The work aims to engage the imagination by making intimate the viewers’ own story and the story of the community where they find themselves. It encourages the viewer to interpret and make meaning of the human experience of the sacred and the ordinary.

Ultimately I believe art is beyond interpretation; it opens human beings to the mysterious, sacred, religious, holy. Veronica Brady elaborated well this role for Art:

Art leads us in Patrick White’s words to ‘ know what we do not know’, to be aware with the whole body, the evidence of all the senses, not just of the mind but also with intuition, of the sense of what cannot be put into words but is experienced intensely and intimately. In this sense it has to do with faith commitment to realities at present unseen rather than with the certainties of ‘religion’ as we have defined it. To the extent that it generates a sense of strangeness, of otherness, to the extent that it points in the direction of the holy… that mystery which makes us tremble yet draws us to it with intense longing, symbolised by the Burning Bush of Exodus, burning yet never consuming itself (Caught in the Draught: On Contemporary Australian Culture and Society, 1994, p.223).

I conclude with a few other examples of my work for you to contemplate from these perspectives. For further information, see my website: www.philipcooper.com.au.