Rite and Vessels

Rite and Vessels

The form of communion vessels reveals something of our ritual practice. Conversely, change in the way we receive communion necessitates change in the kind of vessels we use. The small chalice and paten used so frequently over recent centuries are designed exclusively for the priest’s communion. Early communion vessels give us a glimpse of a differently organised communion rite in which everyone drank from a common cup and received part of the broken bread. These vessels carry a different understanding and liturgical theology.

The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing in the blood of Christ? The loaf that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ? Because there is one loaf, we who are many are one body, for we all partake in the one loaf (1 Cor 10:16-17).

The early 9th century chalice of Ardagh kept in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin has already featured in another article on this CatholicArt website (link). The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC displays the chalice of Abbot Suger of St Denis near Paris; in the 12th century, the abbot set an ancient sardonyx cup with a gold and gem-studded rim, handles, node and base; its diameter is 12 cm. These are not isolated examples of large-size vessels. Our illustration here shows part of the 1980 discovery of liturgical vessels at the monastic site of Derrynaflan, near Cashel in Tipperary. They date from the 8th/9th century and include not only a large size common cup for communion but also a paten meant for a loaf of bread to be broken.

Derrynaflan Chalice and Paten (1)

The Middle Ages saw the development of the ‘private Mass’ and the design of eucharistic vessels changed accordingly. The Churches of the Reform, however, restored communion from the cup to all the people.

One way of understanding the celebration of Eucharist in the 1552 Book of Common Prayer is to see a shift of focus from consecration to communion. Sufficient bread and wine was placed on the altar for the communion of all. After Christ’s words of institution and his admonition to Do this in memory of me, priest and people receive communion in the form of both bread and wine. ‘Do this’ is thus directly related to ‘Take and eat’ and ‘Take and drink’. The Lord’s Prayer and a prayer of offering follow communion.

The new practice of communion under both kinds required new communion vessels. Previously, the priest required only a small amount of wine and a single host for himself, while the people – when they received their annual communion – received the host alone from the reserved sacrament kept in the tabernacle. With the reformed communion practice in the sixteenth century, larger dishes and bigger deeper cups were required and probably also a flagon with which to refill the cups during communion.

English Communion Vessels 16th and 17th centuries.

Many of these vessels were made at the beginning of the reign of Elizabeth I.

The footed paten would also serve as a chalice lid.

Top right: National Gallery of Victoria, Felton Bequest 1973.

From the beginning of the twentieth century, at the instigation of Pope Pius X, frequent communion was encouraged in the Catholic Church. Sodalities were formed in parishes to urge members to monthly communion. Then, in 1963, the liturgy document of the Second Vatican Council spoke of full, conscious participation by all in the action of the liturgy. To this end, the Council encouraged people’s communion from what was consecrated on the altar (rather than from hosts kept in the tabernacle) and it opened the way for communion under both kinds (SC 55). As once for the Churches of the Reformation, so now for the Catholic Church, a new communion practice required new communion vessels.

The Council pointed out that the Church has always been a friend of the fine arts, has ever sought their noble help, and has trained artists with the special aim that all things set apart for use in divine worship are truly worthy, becoming and beautiful, signs and symbols of the supernatural world (SC 122).

From January 1970, we would begin to pray in Eucharistic Prayer IV: by your Holy Spirit, gather all who share this one bread and one cup into the one body of Christ, a living sacrifice of praise. The General Instruction of the Roman Missal reinforced the Vatican II principles, offering guidelines on the eucharistic elements, and spelling out the details about the design and fabrication of communion vessels. The importance of the sacramental sign is emphasised. It is desirable that the eucharistic bread, even though unleavened and made in the traditional form, be fashioned in such a way that the priest at Mass with the people is truly able to break it into parts and distribute these to at least some of the faithful… The gesture of the fraction or the breaking of the bread… will bring out more clearly the force and importance of the sign of the unity of all in the one bread, and of the sign of charity by the fact that the one bread is distributed among the brothers and sisters (GIRM 321).

Likewise, the Missal affirms that Holy Communion has a fuller form as a sign when it takes place under both kinds. For in this form the sign of the eucharistic banquet is more clearly evident and clearer expression is given to the divine will by which the new and eternal covenant is ratified in the Blood of the Lord, as also the connection between the eucharistic banquet and the eschatological banquet in the Kingdom of the Father… the faithful should be instructed to participate more readily in this sacred rite by which the sign of the eucharistic banquet is made more fully evident (GIRM 281-282).

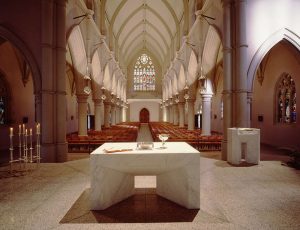

During the 1980s, the refurbishment of Brisbane’s Cathedral of St Stephen took shape. Part of the program included the provision of new vessels and vestments for the liturgy. To express the sign of unity in visible form, a large chalice and a large vessel for the bread were commissioned. These alone would stand on the altar during the Eucharistic Prayer, along with a flagon to hold the extra wine for consecration if necessary. They were designed to harmonise with the altar, symbol of Christ.

At the breaking of the bread during the Communion Rite, additional vessels for the communion of the people, plates and cups, would be brought to the altar and the bread would be broken and divided up and the wine poured out.

These communion vessels, along with the altar candelabra and the Paschal Candle stand, were commissioned from one of the best gold and silversmiths in Australia, Hendrik Forster. He was born in Munich in 1947 and came to Australia when still in his 20s. His work is held in National, State and regional galleries. The vessels are handcrafted from silver and the chalices have a gold plated interior. Forster’s work for the Cathedral of St Stephen admirably fulfils the requirements of the Roman Missal.

Among the requisites for the celebration of the Mass, the sacred vessels are held in special honour, and among these especially the chalice and paten, in which the bread and wine are offered and consecrated and from which they are consumed. Sacred vessels should be made from precious metal… (GIRM 327). For the consecration of hosts, a large paten may fittingly be used, on which is placed the bread both for the priest and the deacon and also for other ministers and for the faithful. As regards the form of the sacred vessels, it is for the artist to fashion them in a manner that is more particularly in keeping with the customs of each region, provided that the individual vessels are suitable for their intended liturgical use and are clearly distinguishable from vessels intended for everyday use (GIRM 331-332).

A decade after the restoration of St Stephen’s, after the tragic fire that destroyed St Patrick’s Cathedral at Parramatta, a new cathedral was to be built there and new art, vessels and furnishings were to be commissioned. An Art Advisory Committee was established in conjunction with the architect Romaldo Giurgola so that art and architecture would integrated into a unified whole. Again this diocese turned to Hendrik Forster.

He designed and made a large-scale chalice and paten, a flagon, and twelve communion dishes and twelve cups. This time the commission was even broader than Brisbane’s. It included also a monstrance and ciborium, cruets for water and wine, vessels for the lavabo, containers for the holy oils and vessels for anointing and the sprinkling of water, a thurible and incense boat, a baptismal shell and a diocesan crozier – 65 pieces in all.

Chalice and communion cup.

Communion cup and plate.

Flagon and cruet.

St Patrick’s Cathedral, Parramatta.

Sterling silver, gold plate, stainless steel, polymer nylon.

Prototypes held in Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences (Powerhouse) Sydney.

Cardinal Cassidy and Bishop Kevin Manning

Forster’s chalice designs for both cathedrals are robust enough to be passed from hand to hand and have a lip that is comfortable for the communicant to drink from and easy for the minister to wipe. Forster has given us two outstanding sets of vessels, well adapted to the renewed Catholic communion rite. But the designs are profoundly traditional. The large Brisbane chalice has thumb handles on the sides to facilitate holding it up at the elevation. This design element and the size and shape of the bowl are taken from the famous Irish chalices of Ardagh and Derrynaflan. from 9th century Ireland. The design of the Parramatta paten is derived from the early paten found at Derrynaflan.

We have featured the work of Hendrik Forster for the cathedrals of Brisbane and Parramatta. Many parishes have also commissioned new sets of communion vessels for the liturgy. Australia has led by example in implementing in parish life the principles of Vatican II.

Other countries have not had this same liturgical experience. In many parts of Italy, for example, it would be uncommon for people to be offered communion from the cup, to receive bread broken from a larger loaf, or to receive communion consistently from the altar rather than the tabernacle. Consequently when the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments released it regulatory document on the eucharistic practice in 2004, its perspective may have been limited. The Congregation is concerned to remedy ‘abuses’: Redemptionis Sacramentum: on certain matters to be observed or to be avoided regarding the most holy Eucharist.

The document does affirm the desire to have people receive hosts consecrated in the same Mass (RS 89) and repeats the sacramental value of communion under both kinds (RS 100); but it is keen to avoid even a small danger of mishap. It lists quite a number of circumstances when communion should not be offered from the chalice (RS 102). On the symbolism of the ‘one cup’, the document says, it is praiseworthy, by reason of the sign value, to use a main chalice of larger dimensions together with smaller chalices (RS 105) but then continues: however, the pouring of the Blood of Christ after consecration from one vessel to another is completely to be avoided, lest anything should happen that would be to the detriment of so great a mystery. Never to be used for containing the Blood of the Lord are flagons… (RS 106).

On eucharistic vessels, the Congregation reaffirms the need to use solid, noble materials: It is strictly required that such materials be truly noble in the common estimation within a given region, so that the honour will be given to the Lord by their use, and all risk of diminishing the doctrine of the Real Presence of Christ in the eucharistic species in the eyes of the faithful will be avoided. Reprobated, therefore, is any practice of using for the celebration of the Mass common vessels, or others lacking in quality, or devoid of all artistic merit or which are mere containers, as also other vessels made from glass, earthenware, clay, or other materials that break easily… (RS 117). The beautiful handcrafted vessels of Hendrik Forster for the cathedrals of Brisbane and Parramatta follow these rules to the letter and are examples of the highest artistic standards.

However, it is a pity that the local evolution in the form of eucharistic vessels has not been fully recognised in Redemptionis Sacramentum. The large chalice and flagon commissioned from Forster were specifically designed for liturgical use, to be in keeping with the customs of the region; they are clearly distinguishable from vessels intended for everyday use (GIRM 332). The consequence of the 2004 ruling is that multiple chalices are now placed on the altar at the preparation of the gifts and the wine is poured into them from the flagon before the Eucharistic Prayer begins.

TOM ELICH, chair of the National Liturgical Architecture and Art Council, director of Liturgy Brisbane.

(1) Images of Derrynaflan vessels. Paten: Creative Commons (Ancient History Encyclopedia). Chalice: © Stair na hÉireann/History of Ireland website.