The term ‘liturgical banner’ evokes for most Catholics the static seasonal decorations we see on the walls of our churches. In the 1970s, these were often local amateur productions made by gluing felt cut-outs onto coloured hessian. More recently they have been mass-produced by religious goods companies. However, I would like to reflect on the liturgical banners which are carried in procession.

The term ‘liturgical banner’ evokes for most Catholics the static seasonal decorations we see on the walls of our churches. In the 1970s, these were often local amateur productions made by gluing felt cut-outs onto coloured hessian. More recently they have been mass-produced by religious goods companies. However, I would like to reflect on the liturgical banners which are carried in procession.

This form of liturgical art has a long history in the Catholic tradition but in many cases today the art work lingers in a by-gone era; frequently the style of these banners has almost nothing to do with contemporary art of the 21st century. They were often used for processions on Marian feasts or for those associated with the Blessed Sacrament. Parishes that have this kind of banner should take care to conserve them and store them safely, and even, on occasion to use them for an appropriate feast or devotion.

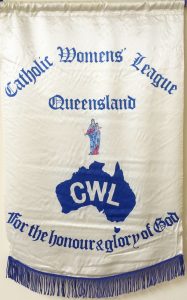

Sometimes, processional banners say less about a feast or season and more about the identity of a religious group or sodality. These were commonly seen in the Corpus Christi processions and were carried by parish and diocesan associations, religious orders, or schools. Today, banners carried in procession at a school Mass will often identify the various ‘houses’ into which the students are divided. These banners can enliven a liturgical procession but are not really ‘liturgical banners’ celebrating a liturgical season, feast or an aspect of faith.

Sometimes, processional banners say less about a feast or season and more about the identity of a religious group or sodality. These were commonly seen in the Corpus Christi processions and were carried by parish and diocesan associations, religious orders, or schools. Today, banners carried in procession at a school Mass will often identify the various ‘houses’ into which the students are divided. These banners can enliven a liturgical procession but are not really ‘liturgical banners’ celebrating a liturgical season, feast or an aspect of faith.

In revisiting the tradition of procession banners in liturgical processions, Australian parishes can learn a lot from many of the ethnic communities who naturally adopt these forms of religious expression. Street processions with banners are often associated with our wonderfully multicultural Church. Italian communities with a connection to Sicily, for example, celebrate an annual procession for their Three Saints (Alfio, Filadelfo, Cirino). For Filipino Catholics, this form of religious expression springs forth quite naturally on a number of feast days, not only associated with Christmas and Easter but also local festivities such as the Holy Infant or the Black Nazarean. Processional banner are often paired with special costumes, adding to the flair and colour.

Left: Black Lives Matter, Cairns 2020. Right: Change the Rules Rally, Melbourne 2018.

People in Australia also readily take to the streets to demonstrate. In order to make a point or publicise a cause – whether it is a political matter or an issue of social justice – the placards and banners come out, and the ritual chanting, singing and marching begins. These events are full of energy and commitment and provide another cultural space we might draw on in the revitalisation of liturgical processions.

Renewing the Religious Tradition

Against all this background, we might ask ourselves how we could rehabilitate the tradition of processions in the life of the Australian Church and how we could engage with contemporary art in doing so. These questions were prompted by an encounter with the art of Fernando do Campo.

Born in 1987 in Argentina, do Campo now lives and works in Sydney where he is a lecturer at UNSW Art and Design. He has spent time working in archives, especially on the acclimatisation of plants and animals in Australian colonial times. He explores how humans and animals interact and live together. His recent exhibitions in Hobart, Sydney and Perth (To Companion a Companion) explore human-bird relationships with particular reference to the laughing kookaburra. These birds were introduced to Tasmania and Western Australia in an expression of nationalistic fervour in the decades before Federation. Do Campo points out that Australia itself is a colonial invention and our landscape was and will continue to be a construct. Kay Harrison from UNSW Media summarised do Campo’s exhibition in this way: this project explores the nexus of colonialism and nationalism, human and non-human relationships, and the interplay of meaning and nonsense.

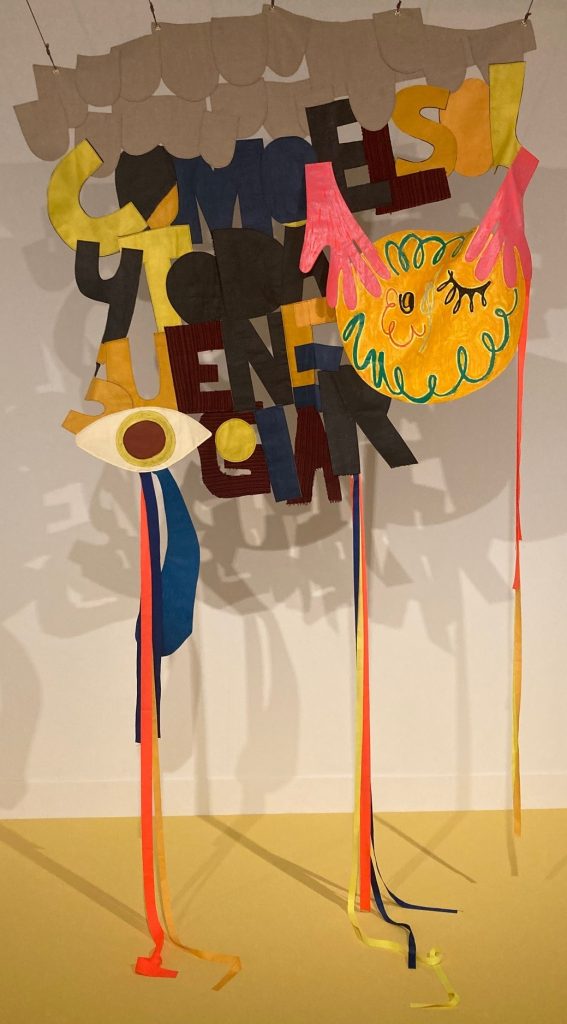

His paintings are colourful panels, either abstract or based on words/lettering. What caught my attention were a series of large abstract banners which he used in his participatory performance art, Who’sLaughingJackass (2020). This was a joyous romping informal event where costumed participants made bird noises with megaphones (beaks). The banners picked up the browns, pinks and blues of the bird’s plumage and, like the paintings, are based on letter forms representing the sound of human and bird calls.

A work like this provoked for me reflection on liturgical processions, not of course on the nonsense play or rollicking fun, but on modes of participation and the role of art in ritual movement and sound. How important is it to have recognisable (and often pious) pictures on our liturgical banners? Like vestments, they will communicate best by their shape and colour, by the way they move, by the opportunity they offer for participation in a liturgical event. Here are some of Fernando do Campo’s banners displayed in the art gallery.

|

|

|

|

We might ask ourselves if we could imagine abstract banners like this being carried in procession for Palm Sunday or St Patrick’s Day, for Corpus Christi or the Good Friday Stations of the Cross. The banners would sway and blow in the wind as the people moved rhythmically in procession, accompanied by instruments and singing. The patterns and colours work equally well from the front and from the back. The colours and shapes, of course, would flow from the occasion and the nature of the procession.

I also came across fabric works by another South American artist, Nadia Hernández, this time from Venezuela. She was also born in 1987 and is also based in Sydney. She is well-known for her hard-edged graphics in bright colours. She designed the banners, posters and publicity for the Sydney New Year’s Eve celebration in 2017 and has painted several street murals, notably her public art To be Free is to have no Fear in Loftus Lane, Sydney.

Her work is shaped by the difficult political situation in Venezuela, but she approaches the narrative of social justice and politics through personal family motifs. In a textile mixed media work of 2020 (left), she uses a description of her grandmother which came from one of her cousins: Como el sol y toda su energia / Like the sun and all its energy. Although this is a gallery piece, it references processional banners and might stimulate ideas for creating them.

Hernández uses her works and words as ‘non-violent weapons’ to fight a regime which has stripped so much from human relationships, culture and the arts. Below is a 2018 work based on a poem written by her grandfather: Cae el telón de la noche, un ejército de luces entrtejen la ciudad / The curtain of night falls, an army of lights interlace the city.

I suggest that processional banners, created by contemporary artists, would offer us new avenues for active ritual participation by the faithful and suggest new possibilities for the interaction of liturgy and the visual arts. This need not be just for devotional festivals or public processions on feast days. Why could we not incorporate elements of this tradition into our regular entrance procession at Sunday Mass? We regularly use a processional cross and candles: why not add one or more processional banners to provide colour, movement, a seasonal connection, and undoubtedly a festive spirit.

The fact that participative performance art sounds like fun in no way compromises its seriousness of purpose. Many cultures would affirm that colourful religious processions are both attractive communal events and a profound expression of faith.

Rev Dr Tom Elich, former chair of the National Liturgical Architecture and Art Council, is director of Liturgy Brisbane.