John Hawes and Margaret Rope

John Hawes and Margaret Rope

That is why artists, the more conscious they are of their ‘gift’, are led all the more to see themselves and the whole of creation with eyes able to contemplate and give thanks, and to raise to God a hymn of praise (John Paul II, Letter to Artists, 1999, no 1).

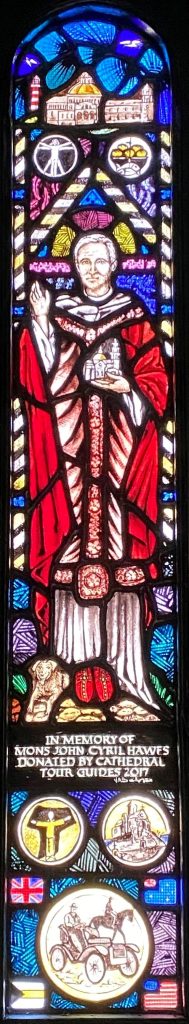

Priest and architect, John Cyril Hawes (1876 – 1956) wrote in 1950 that he did not so much design his buildings, but rather he discovered them.

I got a vision, a hunch of my imagination… some misty vision of fleeting beauty… the rhythm of a poem in stone. Humbly, to take a similitude from the sublime master Michelangelo who, facing a huge block of shapeless marble, saw with a prophet’s eye an angel in it, started with furious blows of mallet and chisel to liberate the angel (John Hawes, “Scratchings of a Cat Islander – An Attempt to Rediscover Reality in Architecture”, Liturgical Arts (Vol 19 no 1).

I got a vision, a hunch of my imagination… some misty vision of fleeting beauty… the rhythm of a poem in stone. Humbly, to take a similitude from the sublime master Michelangelo who, facing a huge block of shapeless marble, saw with a prophet’s eye an angel in it, started with furious blows of mallet and chisel to liberate the angel (John Hawes, “Scratchings of a Cat Islander – An Attempt to Rediscover Reality in Architecture”, Liturgical Arts (Vol 19 no 1).

The art and architecture of John Hawes, conceived in contemplation, echoes in our time a symphony of praise to God able to be heard by those who likewise perceive with a contemplative mind and heart.

In the tradition of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Hawes was not only the architect of his buildings but also designed (and sometimes personally executed) its furnishings and art, both religious and liturgical. At other times, he engaged or worked collaboratively with other Arts and Crafts Movement artists, sculptors and stained glass window artists, such as Philip Lindsay Clark, Martin Travers and Margaret (Marga) Rope.

Margaret Agnes Rope (1882 – 1953) was born in Shrewsbury. Like Hawes, Margaret was born an Anglican but, with her mother and four of her five siblings, entered the Catholic Church in 1901. She was studying at the Birmingham School of Art, specialising in stained glass, under the Arts and Crafts Movement teacher, Henry Payne. In her twenties, she was considered ‘spirited’ and unconventional, wearing short hair, smoking cigars and riding her motor bike. After World War I, she received commissions for memorial windows and much of her most important work is found in Catholic churches. In 1923, Margaret became a Carmelite nun, but this did not stop her creation of stained glass.

John Hawes most likely came to know Margaret through his friendship with her brother, Henry. Both John and Henry trained for the Catholic priesthood at the Beda College in Rome, and were ordained together on 27 February 1915 at St John Lateran Basilica, Rome.

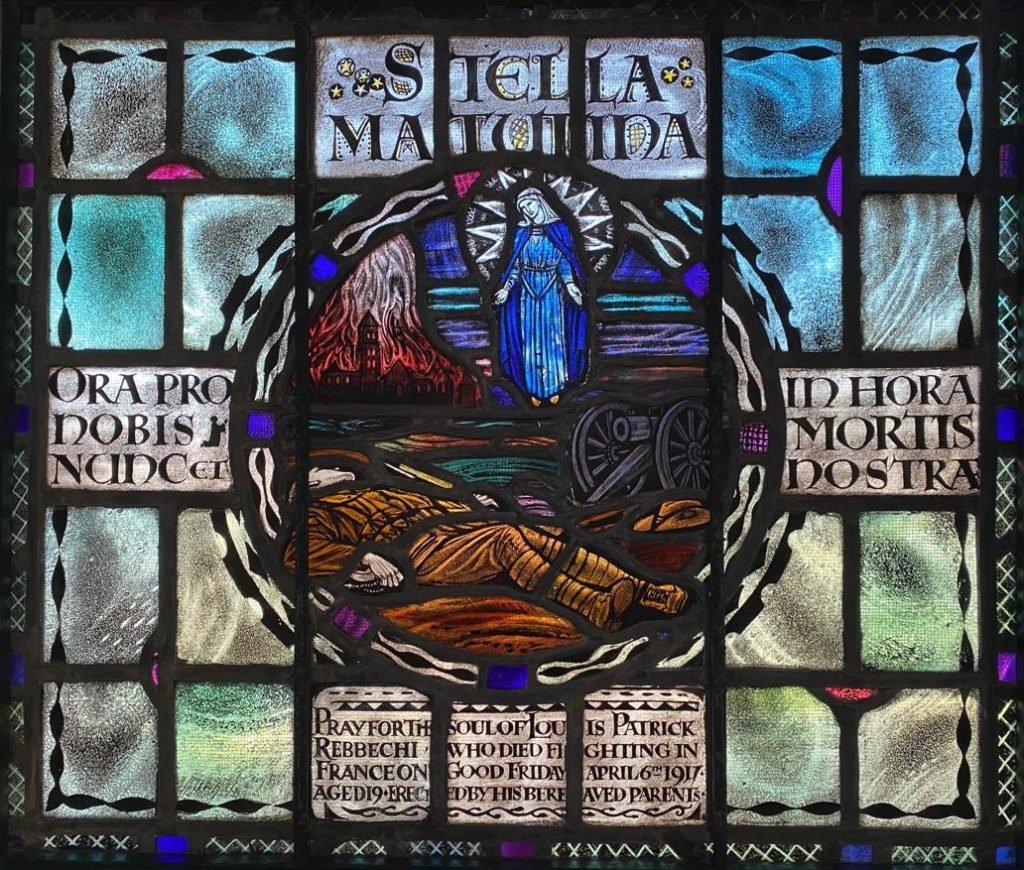

In Hawes’ magnum opus, St Francis Xavier Cathedral in Geraldton, six stained glass windows can be attributed to the combined art and craft of John Hawes and Margaret Rope. The Geraldton Diocesan Archives contains several stained-glass cartoons drawn and painted by Hawes which were then forwarded to Margaret for her to enhance and execute. Of these, one window is so poignant that it often brings a lump to my throat when I contemplate it or attempt to explain its story and iconography to cathedral visitors. It is a memorial to Louis Patrick Rebbechi.

John Hawes’ original cartoon of the Rebecchi Window and Margaret Rope’s stained glass artistic rendition.

A Contemplation

The window consists of three panels, a vertical triptych read from bottom to top. As a whole, it is like a rising column of smoke with flames erupting in the topmost arched panel, destructive yet purifying.

The lower panel is a square containing four inscriptions that evocatively form a cross. In the centre is pictorial medallion and around it are small squares of grey, green and brown leaded glass, depicting the swirling artillery smoke and poisonous chlorine gas of the Great War.

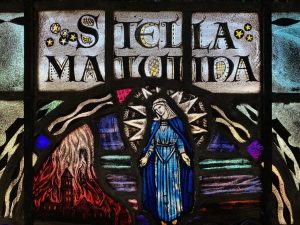

The panel is titled above the central medallion, Stella Matutina (Morning Star), a title of the Virgin Mary in the litany of Loreto.

Left and right of the medallion is the supplicatory second half of the Hail Mary, Ora pro nobis… nunc et in hora mortis nostrae (pray for us… now and at the hour of our death).

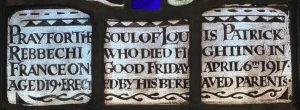

At the bottom is the memorial inscription that draws one into the story. It tells of the grieving parents who lost their 19-year-old son, Louis Patrick Rebbechi, on, of all days, Good Friday 6 April 1917; he was fighting in France on the Western Front.

At the bottom is the memorial inscription that draws one into the story. It tells of the grieving parents who lost their 19-year-old son, Louis Patrick Rebbechi, on, of all days, Good Friday 6 April 1917; he was fighting in France on the Western Front.

In contrast to the swirling smoke and gas surrounding it, the central medallion provides a vivid glimpse of the truth of war: in the midst of death and destruction, faith and hope reign eternal.

Here we see Louis lying dead on the battlefield, with his rifle to his left and his rosary beads clasped in his right hand, a symbol of his faith. Before the steel grey of the canon lies Louis’ Australian Imperial Force slouch hat, with its rising sun badge, another symbol of our eternal hope in the risen Son.

In the background is a village on fire, including its church and campanile. The destruction of war is both material and spiritual. Questions churn: “Why does God permit war and suffering? Can faith survive? Is God dead? Will the bells of the campanile ever sound out again to call people to prayer and faith? Will they hear?”

In the background is a village on fire, including its church and campanile. The destruction of war is both material and spiritual. Questions churn: “Why does God permit war and suffering? Can faith survive? Is God dead? Will the bells of the campanile ever sound out again to call people to prayer and faith? Will they hear?”

Over this scenario the Morning Star rises. The Blessed Virgin Mary, dressed in celestial blue and victoriously crowned with stars, stretches out the welcoming arms of a grieving mother. Even in the darkest of places, God’s light penetrates, bringing hope in despair. But look carefully. While the face and hands of Mary are illuminated in white heavenly light, her feet remain earthly flesh in colour. This same mother, who stood at the foot of the cross of her Son Jesus in the hour of his death, is firmly grounded in this world and stands praying over Louis Patrick Rebecchi at the hour of his death.

The middle window paints for us the heavenly victory. It is called Janua Coeli (Gate of Heaven), another petition from the Litany of Loreto. In the background is the Lamb of God with the banner of the resurrection, standing aloft amidst the multitude of palm-waving saints who have gone before us. They are surrounded by radiant light and the angelic seraphim.

The foreground touchingly illustrates Louis Rebecchi’s entry into heaven. His soul – represented by the orb containing Louis kneeling, dressed in his AIF khaki uniform – is being presented by an angel to his heavenly mother, the crowned Virgin Mary.

In the surrounding glass squares, the colours of celestial blue suggest the swirling clouds of heaven. Four panes contain symbols of heaven and victory: the harp and incense, the crown and the palm.

Michelangelo may have liberated his angel from the block of marble. In this window, thanks to the combined insight of the inspired Arts and Crafts artisans John Cyril Hawes and Margaret Rope, we can again contemplate our liberation in the risen Christ.

To discover more about Margaret Rope and John Cyril Hawes, please visit https://margaret-agnes-rope.co.uk/ and https://www.monsignorhawes.com/

Robert Cross, priest and chancellor of the Diocese of Geraldton, is also Director of Heritage. He has studied extensively the work of Monsignor Hawes.