Over the last twenty-five years, Australian artist, Ron Mueck (b. 1958), has become well-known for his hyper-realistic sculptures, generally of the human figure either much larger or smaller than life size. Every hair is painstakingly inserted in an eyebrow or a stubbly beard. Whether it is an enormous boy or pregnant woman, whether it is a miniature image of his dead father laid out naked, the sculptures create a sense of awe, wonder and contemplation in the viewer.

Over the last twenty-five years, Australian artist, Ron Mueck (b. 1958), has become well-known for his hyper-realistic sculptures, generally of the human figure either much larger or smaller than life size. Every hair is painstakingly inserted in an eyebrow or a stubbly beard. Whether it is an enormous boy or pregnant woman, whether it is a miniature image of his dead father laid out naked, the sculptures create a sense of awe, wonder and contemplation in the viewer.

Currently on display at the National Gallery of Victoria’s Ian Potter Centre for Australian Art is a work of Ron Mueck which the gallery commissioned for its 2017 Triennial. Entitled Mass, it comprises 100 huge human skulls cast in resin and each finished by hand to make it unique (adding teeth, for example). The work fills an entire room. However it is not only monumental, it is also eerily confronting.

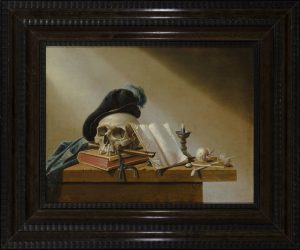

Left: Harmen Steenwijck, Vanitas (Dutch, mid 17th century)

Left: Harmen Steenwijck, Vanitas (Dutch, mid 17th century)

The human skull has long been the subject of meditation on the meaning of life and death. Carved on tombstones or furniture, painted on canvas or the pirates’ flag, formed out of papier-mâché for the Day of the Dead procession, it serves as a memento mori, a remembrance of death. This was a prominent theme in art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In Dutch still-life painting, it was often combined with wilting flowers or over-ripe fruit, with the hourglass or an extinguished candle, to provoke reflection on the fragility of life and the ever-present reality of death. Sometimes these elements are even found in the bottom corner of a fashionable portrait. Life was lived in view of death and judgement.

In Christian iconography, the skull often appears at the foot of the crucified Christ, not only a reference to Golgotha as ‘the place of the skull’, but also a representation of the skull of Adam who was said to be buried at that place.

In Christian iconography, the skull often appears at the foot of the crucified Christ, not only a reference to Golgotha as ‘the place of the skull’, but also a representation of the skull of Adam who was said to be buried at that place.

Mueck’s Mass, however, is more terrifying still, not only because of the frightening scale of the work, but because of the seemingly careless heaping up of the skulls. It evokes the monstrous slaughter of war and persecution, and the consequent dumping of the dead in mass graves: we have seen images like this from Cambodia or Rwanda, from the Holocaust, from conflict in Syria or the Ukraine. It evokes also the horrors of pestilence: from the Black Death of the Middle Ages to the immense human loss of life in twentieth-century pandemics and famine. Such layers of meaning force us to consider the state of the world and our care of creation, and provoke us to work for peace and justice for all human beings.

Confronting death calls us to conversion of life.

Rev Dr Tom ELICH is Director of Liturgy Brisbane.