My name is Olga Bakhtina. Once in a while, people ask me why I paint Christian scenes. Every time the question comes up it surprises me. What does make a mostly self-taught contemporary artist like me paint Christian stories when so few people do?

My name is Olga Bakhtina. Once in a while, people ask me why I paint Christian scenes. Every time the question comes up it surprises me. What does make a mostly self-taught contemporary artist like me paint Christian stories when so few people do?

The answer isn’t short or simple. It begins – like any good story – a long time ago.

I was born in the USSR in 1973, behind the iron curtain, and raised in a time of renewed religious persecution. Russia in the 1970’s saw existing anti-religious legislation strengthened and a strong anti-religion propaganda campaign. Hundreds of doctoral and masters’ dissertations were written on scientific atheism and dedicated to the criticism of religion.

At schools, colleges and universities collective brainwashing took place, aimed at eliminating any last remnants of religion from the ‘progressive Soviet society’. It almost succeeded. Only 4% of the population attended church – mostly elderly people born before the Russian Revolution of 1917. My parents had me baptised as an infant in secret. It could have cost them their jobs. Probably worse. I think my grandmother was insistent.

When the USSR collapsed and the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, people had lost their belief in socialism and what it stood for. But more importantly, people were no longer afraid of being persecuted for their beliefs. Many Russians turned back to religion as an island of safety and a compass for their lives. In the years that followed, the Russian Orthodox Church became a powerful adviser and ally to the government.

In 1999, I left Russia for a new life. The journey started in the UK, but soon took my family and me to the Philippines, the Sultanate of Oman and to Brisbane. I finally embraced painting and now can’t imagine life without it. Though passionate about drawing and painting since childhood, I never had an academic art education. In 1990’s Russia, my parents thought it was a clear path to starvation. Instead I got a master’s degree in linguistics and teaching.

So, baptised in secret, raised an atheist, travelling and living in culturally diverse countries (including 4 years in an Islamic country)… why do I paint Christian subjects?

Simply, because faith is a gift. And because a religious painting is not just created with paint and brushes. It is created with paint, brushes and prayers.

The history of art shows how deeply intertwined are art, religion and society. A vast part of our art heritage was devoted to Christianity, art commissioned and preserved by the Church. The more I studied art history, the more I became interested in theology. Two years ago, I went back to study History of Art at the University of Queensland.

In my own art practice, I find inspiration in Byzantine icons as well as Early Renaissance work. One of my strongest experiences was visiting the crypt under the stunning Duomo in Sienna, Italy. The cathedral is a great tourist attraction, but not many people visit the 13th century crypt. The crypt was full of construction rubble for more than 600 years and was rediscovered in the late 1990s. The frescoes, original in design and vivid in colours, contrast with the rich extravagance of the cathedral above. Their form is simple, their message straightforward. One can feel the hope these frescoes brought to the pilgrims in what were gloomy and desperate times. This art is more than a pretty picture on the wall.

Each of my religious works is a spiritual exploration and a prayer.

Annunciation is one of my favourite paintings. I tried to achieve a sense of mystery through colour, light and an atmosphere of tranquillity. It is the quiet stillness that one can see in Early Renaissance art.

Mother and Child was an experiment with an Early Renaissance style, staying true to myself by adding a touch of Modernism. I mentioned my paintings are my prayers: I have three children and so have a number of variations on this theme, both in oil and charcoal.

Usually, when I plan a painting, I make several charcoal sketches, experimenting with possible compositions. Later, some of these sketches turn into paintings, some stay as the completed works. Working in charcoal is a special experience, sensitive and rather introverted. There is something prehistoric in having hands dirty with charcoal again – remembering when a drawing on a cave wall was a prayer for a good hunt or a way of giving thanks.

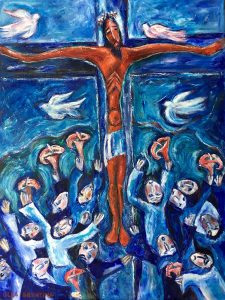

My first Christian artwork, Resurrection, was painted almost 6 years ago, when my father-in-law was dying. Erik, my husband, flew urgently to Netherlands; I couldn’t go with him as my elderly mother was visiting from Russia. But on some level, I did. Resurrection was my goodbye and prayer for my father-in-law, as well as a prayer for my husband. An attempt to help him to hold on, and stay strong, to make him feel that I was close. Art does magical things after all. When people ask me why there are ducks on the painting, I can’t give a clear answer. Maybe, not everything has an answer.

Why, in times of despair when all the other sources of hope are empty, do even atheists ask for divine help? Or, in the middle of a sleepless night when you feel the world’s vulnerability and imperfection, why do you ask for forgiveness or protection for your loved ones? We all need hope, forgiveness, faith. Blue Praye’ is a meditation on this. The painting took a long time to complete. On good days, the lilies would turn into innocent white; on lesser days, they would become bloodthirsty, sinful red. In the final work, they are a mixture of both — as are all of us.

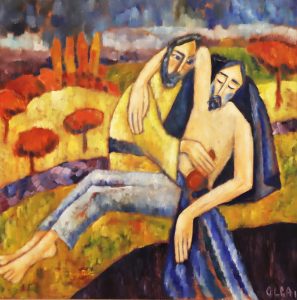

The parable of the Good Samaritan has inspired artists for centuries. It has been painted and drawn thousands of times, from the great masters like Delacroix and Rembrandt to children learning the values of Christianity in kindergarten. I painted three different versions of Good Samaritan. The first won the Conrad Gargett Art Prize in the 2016 COSSAG Art awards at the Cathedral of St Stephen in Brisbane. Its colours are bright and happy, reminiscent of stained glass in church windows and shimmering Byzantine mosaics. Bold brushstrokes charge the painting with a unique energy. The painting’s message is clear: There is mercy in this beautiful world.

The painting was purchased by Bishop Anthony Randazzo for Holy Spirit Provincial Seminary when he was rector. In 2021, Cengage Learning Australia published it in a textbook for high school students studying religion. The National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, also included it in their catalogue for the exhibition The Double: Identity and Difference in Art since 1990.

Jesus Carrying Cross is another painting from the same year and executed in a similar style. It is also at Holy Spirit Seminary.

Although I often revisit a themes in my paintings, I try not to repeat myself, but further explore the topic, working on variations and refining my pictorial language. During 2021, I painted two more versions of the parable of Good Samaritan, in a different style and manner, investigating different attitudes and facing new artistic challenges.

The challenge is to create a graphic parable, to express the idea in a simple narrative form as Jesus himself was telling it. The parable is shaped up into the well-proportional message, beautiful in its simplicity: Help.

These paintings are also a study in form. They are about geometry and the repetition of the shapes in the design: the similarities in the roundness of Samaritan’s turban, the trees, and the forms of the donkey; the repetition of the shape of the lily and the donkey’s ears. The intersection of verticals and diagonals is the base for the geometry and harmony.

From an art perspective, any painting is about designing a picture and discovering how to take from the scene the forms that are needed, how to let go of the ones that are not, and then to add what you think is right, like the Crucifixion scene in the background of Good Samaritan with Cross. Thus the picture joins the gospel scene and the artist’s personal vision.

The transformation of water into wine at the wedding in Cana was a special moment, the first ‘sign’ as John called the miracle in his gospel. An extraordinary act, done out of kindness and compassion, it was a sign of Jesus’s glory and a demonstration of God’s love and power. I wanted to create an atmosphere of people enjoying a good party. Jesus is part of this celebration, singing with everyone else, rejoicing in the festivity. I love the rhythmical joy of this painting, and remember Walter Pater’s thought that all art should aspire towards the condition of music. Wedding in Cana won the COSSAG Art Prize 2018.

___________

My primary attraction is to the art of the Early Renaissance with its sense of monumental dignity and lyricism. I am also inspired by modernists like George Rouault and George Braque. Maurice de Vlaminck once said, To be a painter is not a business, any more than to be an artist, lover, racer, dreamer or prize-fighter. As an emerging artist I am still in the search of my own path. Since I started painting, my artistic language has been changing and taking the different directions. Nowadays, I get comments that my brushstrokes have greater freedom and expressive power. I like the ability to change. Art is a journey; for me it is a spiritual exploration, finding meaning and making sense of the world. This is often expressed in religious themes.