My PhD research project at the University of Canberra, Treasured Threads: Ecclesiastical Textiles as Living Heritage of the Catholic Church in Australia (2019), grew out of my BA (Hons) dissertation which was inspired by three fragments of historical ecclesiastical embroidery salvaged from old, worn and damaged vestments made obsolete following the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. Vatican II reduced the number and type of ecclesiastical garments worn by clerics and simplified vestment design. As a result, a large amount of ecclesiastical textile heritage was removed from service. Visiting heritage textile collections and speaking with custodians has uncovered a diverse and unexpected web of community and personal significance and values that connect this living textile heritage to a broader web of local, national and international history and ongoing cultural life.

My PhD research project at the University of Canberra, Treasured Threads: Ecclesiastical Textiles as Living Heritage of the Catholic Church in Australia (2019), grew out of my BA (Hons) dissertation which was inspired by three fragments of historical ecclesiastical embroidery salvaged from old, worn and damaged vestments made obsolete following the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. Vatican II reduced the number and type of ecclesiastical garments worn by clerics and simplified vestment design. As a result, a large amount of ecclesiastical textile heritage was removed from service. Visiting heritage textile collections and speaking with custodians has uncovered a diverse and unexpected web of community and personal significance and values that connect this living textile heritage to a broader web of local, national and international history and ongoing cultural life.

Inventories and surveys of Catholic ecclesiastical heritage indicate that a surprising amount of the moveable heritage of a church is in the form of textiles. While Australia is geographically and temporally distant from the Church’s 2000 year history, it is nevertheless home to richly diverse collections of ecclesiastical artefacts. Vesture and other textiles stored in diocesan archives, parish churches, chapels and secular art galleries and museums preserve centuries of changing liturgical practices, trace the history of design and exemplify traditions of once common but now rarely seen textile arts and crafts.

Perhaps the most distinctive Catholic ecclesiastical textiles are the vestments worn by the clergy. The most recognisable of the sacred vestments is the chasuble. Today the chasuble is a loose open sided-garment worn over an alb, a floor-length white linen or cotton robe with long sleeves, but my research revealed an unexpectedly wide range of chasuble styles. My research uncovered exquisite examples in Australia of seventeenth-century baroque extravagance, eighteenth-century rococo and neo-classical elegance and nineteenth century mediaeval-inspired Gothic revival restraint. They include both the flat Roman-style and also the flowing Gothic chasubles.

The history of the chasuble reflects the ever-changing liturgical, cultural, social, aesthetic and political influences of the times of its manufacture and use. The chasuble grew out of the Graeco-Roman paenula or casula, a conical-shaped poncho-like cloak worn as protection against the weather. Over time this simple garment took on greater liturgical significance, and by the ninth century its use was restricted to priests. The earliest priestly chasubles were simple and without ornamentation, resembling a modern cope sewn closed along the front edges, covering the arms and generally reaching below the knee. The conical shape of the medieval chasuble changed over time in response to changes to the liturgy of the Mass. For example the introduction of the elevation of the host to the Mass liturgy in the thirteenth century led to a major design change. The heavy folds in the ornate brocades popular during this time and constricting nature of the cut of the medieval chasuble made raising the arms difficult so the sides of the chasuble were progressively ‘clipped’ or cut away. Eventually the graceful folds of the original conical chasuble and its mediaeval counterpart became the flat, rigid panels characteristic of the so-called Roman or fiddle-back chasuble of the Renaissance era.

The Renaissance also ushered in a new approach to art and architecture, and its influences extended to the ornamentation of vestments. The flat surfaces of the ‘clipped’ chasuble were an ideal platform for displays of status and power, and the use of brocades and embroidery in silk and gold and silver threads, persisted for several centuries. Regional differences in Catholic Europe produced the short, almost pear-shaped viola chasuble characteristic of sixteenth-century Portugal, the elongated, narrow-shoulder A-shaped chasuble of seventeenth-century Spain and the square cut back commonly found in Italy and France. Following the Council of Trent (1545 – 1563), Charles Borromeo, Bishop of Milan, did much to rein in the extravagance and diversity of contemporary vestments, particularly the chasuble. Borromeo’s quest to return vesture to the more graceful lines of medieval times resulted in what is now known as the Borromean Chasuble – a chasuble nearly reaching the heels with the shoulder width extended to 130 cm. The garment rested once more on the arms. It is interesting to note that what is today called the Roman style did not in fact originate in Rome. It is reminiscent of the cut-away style favoured in northern Europe and objected to by Borromeo.

During the seventeenth century, Gothic and Renaissance styles of church architecture were replaced by the flamboyance of the Baroque and vesture followed fashion: motifs were predominantly floral. Historically, these were times of political struggle and colonial expansion. New worlds were opening up and trade routes expanding. Exotic fabrics such as silks from the East and precious metals and jewels from the New World became the status symbols of the rich and powerful, and were seen as the new ‘best’ materials to acclaim the glory of God. During the eighteenth century chasubles were at their most elaborate, with ostentatious display threatening to overwhelm the inherent dignity and sacredness of liturgical services. The earliest textiles found in Australian collections date from this time.

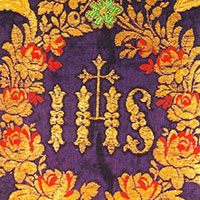

Figure 1: Baroque style chasuble made in Germany and brought to Australia by the Ursuline Sisters. The Sisters were expelled from Germany in the 1870s and, after a brief spell in England, came to Armidale NSW in 1882. The date of manufacture (1714) is coded in the central inscription. The elaborate design is completely hand embroidered and highlights the sewing skills of the sisters who made them (Ursuline Convent Archives, Sydney).

The most common decorative technique used during this period was sumptuous surface embroidery in silk and gold thread. By the mid-eighteenth century Baroque flamboyance had given way to the more fluid lines of the Rococo and the elegance of the Neo-Classical. Gold and silver embroidery was particularly suited to the neo-classical designs popular at this time.

Figure 2: Rococo style chasuble reputed to have belonged to Cardinal Joseph Fesch, Archbishop of Lyons (died 1839), half uncle to Napoleon Bonaparte. The chasuble is in the collection of St Patrick’s Church, Church Hill, Sydney. It most likely arrived in Australia with the Marist Fathers, who were based in Lyons, when they took over the administration of the parish in the late 1860s.

Vestment-making went into decline as revolution swept through Europe, the wealth of the Church was confiscated and convents and monasteries closed. However the early nineteenth century saw Britain lift the restrictions on Catholic worship imposed by King Henry VIII nearly 300 years before. The leading influence on church design and ecclesiastical decoration in England at this time was an architectural style known as Neo-Gothic or Gothic Revival, epitomised by the architect and designer Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin. Pugin, a convert to Catholicism, saw medieval Gothic as the only style worthy of giving glory to God. He revived medieval chasubles and copes, particularly the Borromean style of the mid-1500s. His decorative motifs borrowed much from Gothic tracery and painting.

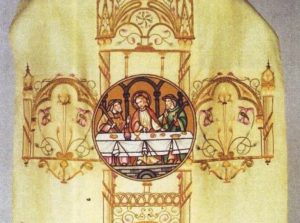

Figure 3: Neo-Gothic Revival chasuble designed by Augustus Pugin c.1850. This historic chasuble is one of the few surviving textiles brought to Tasmania by the first Bishop of Hobartown, Most Rev Robert William Willson (1842-1866). Bishop Willson was a close friend of Pugin who designed many churches and their requisites specifically for the new diocese (Archdiocese of Hobart Archives & Heritage Collection).

Nineteenth century industrialisation played a significant role in reducing the cost and manufacturing time for vestments. Pictorial and narrative designs for fabric and decorative braids were particularly suited to the newly invented Jacquard looms. The best of the intricate figurative and narrative scenes stitched by machine rivalled those produced by skilled hand embroiderers and were cheaper and quicker to produce.

Figure 4: Roman-style chasuble featuring Christ and the Pilgrims at Emmaus. This chasuble is machine embroidered and showcases the design capabilities of expert machine embroiderers in the early twentieth century (Melbourne Diocesan Historical Commission).

The simpler, free-flowing so-called Gothic chasubles championed by Pugin and members of the late nineteenth century Liturgical Movement challenged the established rigid ‘fiddle-back’ styles popular in France, Italy and Spain. Fabrics woven in England and Belgium from this time were characterised by repeating patterns of religious symbols or motifs derived from medieval art and tracery. Gradually the Gothic chasuble spread through Europe. In Australia ‘allegiance’ to Roman style was not as pronounced  as it was in Europe and, at least for the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the Neo-Gothic ‘Puginesque’ revival from England held sway in the colony.

as it was in Europe and, at least for the middle decades of the nineteenth century, the Neo-Gothic ‘Puginesque’ revival from England held sway in the colony.

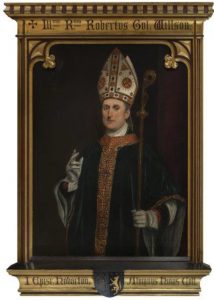

Figure 5: Very Rev Robert William Willson, first bishop of Hobartown, wearing vestments designed by Augustus Pugin. Artist: John Rogers Herbert (ca 1854). (Oscott College, reproduced with permission of the rector, 2018).

Nevertheless, a diversity of styles (both Roman and Gothic) are found in Australian heritage vestment collections. There are examples of decoration influenced by the late nineteenth century French l’art noveau. These designs feature padded goldwork motifs enhanced with spangles and gold metal braid on a silk satin or cloth-of-gold ground fabric. Others harken back to the Neo-Classical and Neo-Rococo designs of the eighteenth century with swirling, stylised floral and foliate motifs embroidered in flat gold thread on plain but brightly coloured silk fabrics.

Figure 6: Left – chasuble featuring generic raised and padded goldwork, seemingly elaborate but mass-produced and relatively inexpensive. (Diocese of Bathurst Archives)

Right – vestment featuring Rococo revival goldwork embroidery, dated 1888; gift from Pope Leo XIII to Most Rev Thomas Joseph Carr, second Archbishop of Melbourne. (Melbourne Diocesan Historical Commission).

The fine workmanship and aesthetics of specialist vestment-makers largely disappeared following the devastation of World Wars I and II. Cheaper cottons and synthetic fibres such as viscose replaced the silks of the nineteenth century and vesture design in general became rather generic. Both Gothic and Roman styles coexisted. Naturally, there were always exceptions, such as the post War hand-made vestments at Jamberoo Abbey.

Figure 7: These chasubles were made by the sisters at Jamberoo Benedictine Abbey, noted for their vestment-making. The cream chasuble (left) is part of a set of vestments made for the centenary of the founding of the abbey in 1948. The ground fabric has been identified as the ‘Cloister’ damask woven by M Perkins & Son, Hampshire, England. The white chasuble (right) was made using fabric from a wedding gown.

One notable exception to the decline in quality design and aesthetics of commercial vesture was the Stadelmaier Company founded in the Netherlands in the 1920s. The company’s designers and craftspeople incorporated traditional symbols and narrative figures referencing firstly the Bauhaus and German Expressionist movements of the 1920s and later 1960s Minimalism. Their preference for the Gothic-style foreshadowed the post-Vatican II call for a return to a simpler, more liturgically based vesture and ornamentation.

Figure 8: The Gabriel chasuble designed and made by the Stadelmaier Company, 1964. The angular figure and bright colours are typical of the company’s designs from this time. Stadelmaier ceased production in 2010 (Melbourne Diocesan Historical Commission).

The liturgical renewal of Vatican II recognised the vestment itself as a symbol of the role of the priesxt and did not need applied symbolic designs. The Council sought ‘noble beauty rather than mere sumptuous display’ (SC 124). With the priest now celebrating the Mass facing the congregation, the large decorative embroidered cross orphreys and pillars that had adorned the backs of chasubles for centuries were largely consigned to history. The liturgical renewal cemented the place of the Gothic chasuble in the Church’s liturgy. New forms of the chasuble were also explored. An interesting, but ultimately unsuccessful, innovation developed by the Stadelmaier Company in the 1960s was the chasu-alb, a simple long sleeved, wide cut floor length vestment which could be worn without an alb and cincture.

Figure 9: A chasu-alb (c. 1975). The unusual design of the decoration reflects the prevailing fashion of brown and earthy tones and firmly places the garment in the 1970-80s (Melbourne Diocesan Historical Commission).

The chasu-alb did however pave the way for Stadelmaier’s next innovation which has been widely adopted and which came to be known as the Nijmegen model (named after the city where the company was situated). It consisted of a wide stole worn over, rather than under, an almost floor-length Gothic style chasuble. Decoration was largely confined to the stole and the ground fabric was often hand woven of natural fibres.

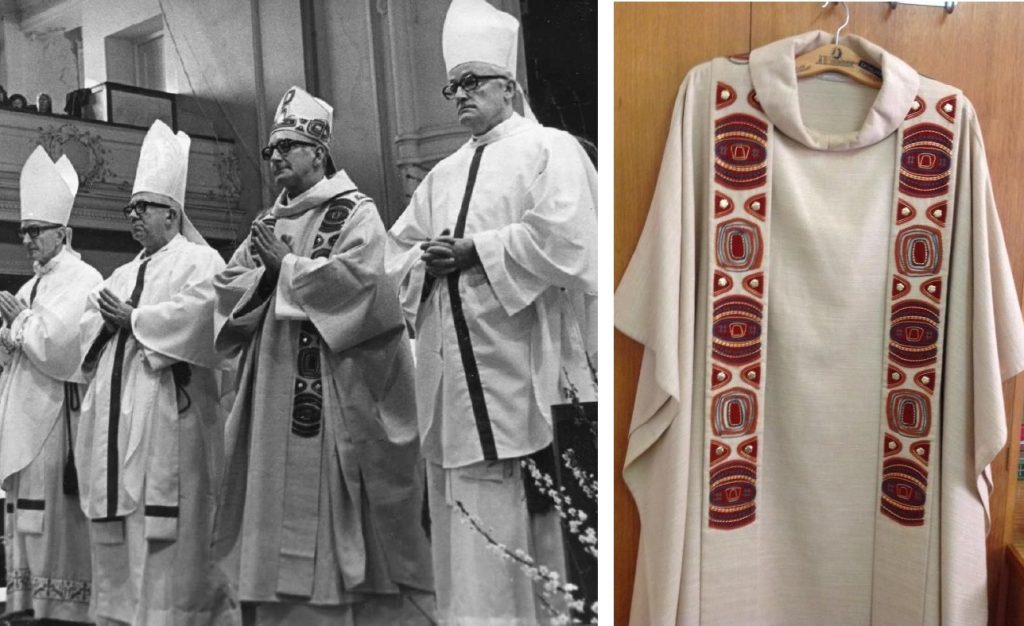

Figure 10: In 1973 Most Rev Guilford Clyde Young, Archbishop of Hobart, wore Stadelmaier Nijmegen model vestments at the Mass for the 25th anniversary of his installation as bishop. The concelebrating bishops wore plain white chasubles (Archdiocese of Hobart Archives and Heritage Collection, and Katholiek Documentatie Centrum, Nijmegen).

The best contemporary vestments are the work of artists and artisans. They contribute to the celebration of the liturgy by their colour, texture and movement. Vesture is not static and today’s vestments, the heritage textiles of the future, are as reflective of and responsive to contemporary liturgical practices and design influences as any from the past.

MARGARET FERGUSON, a chemistry teacher for 33 years, completed a Bachelor of Heritage Conservation with First Class Honours and, in 2019, a PhD from the University of Canberra.