In the same way that churches have been built by Christians for two millennia, the small stone church in the Sydney suburb of Pyrmont, dedicated to St Bede the Venerable, was built by the hands of its parishioners. Much of the sandstone used to build the early buildings of Sydney was quarried in Pyrmont, the same stone that the parishioners cut from the site, shaped and laid to build St Bede’s. They completed the building in 1867 providing for a congregation of about 120 to gather for Mass.

In the same way that churches have been built by Christians for two millennia, the small stone church in the Sydney suburb of Pyrmont, dedicated to St Bede the Venerable, was built by the hands of its parishioners. Much of the sandstone used to build the early buildings of Sydney was quarried in Pyrmont, the same stone that the parishioners cut from the site, shaped and laid to build St Bede’s. They completed the building in 1867 providing for a congregation of about 120 to gather for Mass.

That they chose St Bede as their patron saint links this humble little church with similarly humble stone buildings, the ruins of which stand today on the English Northumbrian coast at the mouths of the rivers Tyne and Wear. Here was one of the most important sites of Christian culture and learning in the 7th and 8th centuries, the monastery of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow. In this place, the English Benedictine monk, the great St Bede (672-735) lived and worked, and wrote his many important books.

In his most famous and influential work, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, he wrote of the establishment of the monastery, describing how the buildings were built by stonemasons and glassmakers brought over from Francia. He maintained that they introduced the craft of the glazier to England.

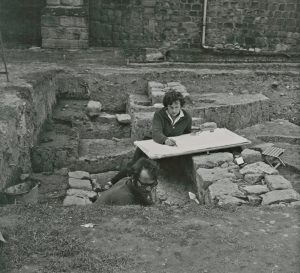

In the year 795, the Vikings sacked the monastery. A part of the devastating damage was the smashing out of the small beautiful coloured glass windows. Over the centuries fragments of this glass lay buried in the ground around the remains of the stone buildings until Professor Rosemary Cramp, archaeologist from Durham University, began her work to uncover them. From 1963 until 1978, she and her team unearthed many thousands of glass fragments which are able to tell us a great deal about the art of the glaziers of this period. In 1981 I had the privilege of meeting with Professor Cramp in her rooms at Durham University where she showed me the collected glass fragments laid out methodically on trays in large chests of drawers.

Many of the pieces of glass had been damaged by the heat of the Vikings’ fire but others looked as though the glazier had just finished working on them. Red, blue, yellow, orange, green and creamy white, the colours were no doubt as vibrant as they were when first made.

We do not know what was depicted in the windows. There is no way of determining this. However we do know that, as with all arts and crafts of this period, everything has meaning and it would be most likely that the windows conveyed aspects of the Christian revelation in images. We can be certain that the colours would have been chosen for their symbolism and that the meaning of the images would have been given emphasis by this symbolism.

One of the first things Professor Cramp drew my attention to was that the glass had been shaped by highly developed craftsmen. Using very fine grozing irons, the glass was carefully chipped away at the edges in a manner not dissimilar to the way a jeweller would shape precious stones. There was nothing crude or rudimentary about the craft on display here. These Frankish glaziers were extremely skilled. They came from a craft tradition that reached its most glorious pinnacle in the windows of the great Gothic cathedrals of France in the 12th and 13th centuries.

These small glass fragments in Durham indicate that the art of the glazier has been a long and important part of the art of the Church. The glass artist remains a significant contributor to the liturgical art of the Church today and there are many practitioners producing fine work for ecclesiastical settings.

Which brings us back to the church of St Bede’s in Pyrmont. As with most such churches of humble origin, employing artists to design images for the windows was not an expense the original parishioners could readily afford. But in 2009, under the guidance of parish priest at the time, Colin Fowler OP, glass artist Paddy Robinson was commissioned to produce designs for most of the windows of the church.

Paddy Robinson in her Finglinna Studio at Sofala in country NSW.

Paddy began her studies in the craft in Belfast, N. Ireland. After graduating, in 1965 she moved to Australia where she worked with local glass artists Stephen Moor and David Saunders before establishing her own Glin Studio in 1973 (Glin is the phonetic first syllable of the Irish Gaelic word for glass). Her current studio is named Finglinna which she established with Neil Finn in 1989 in Peakhurst, Sydney, and which is now located in the NSW country town of Sofala. Paddy lives at studio and works with her glass artist daughter Bridget Thomas. Finglinna’s large output of ecclesiastical works employ a variety of techniques ranging from stained and painted lead light to slumped, laminated, carved, etched and engraved glass.

In the windows for St Bede’s, Paddy has employed traditional lead light techniques with images painted on coloured glass. The images make up an iconographic program based primarily on two scriptural sources:

As a deer longs for flowing streams, so my soul longs for you, O God. My soul thirsts for God, for the living God. When shall I come and behold the face of God? (Psalm 42:1-2)

I am the vine, you are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do nothing. (John 15:5)

The subject matter for the windows was provided by Fr Fowler who was inspired by the 12th century apse mosaic in San Clemente, Rome. The main window depicts the Holy Spirit as the dove in the small quatrefoil light at the top of the arched opening with the cross as the ‘tree of life’ occupying the two lancet lights below. Flowing down from the Holy Spirit are streams of golden light forming the backdrop for the cross from which grows an exuberant vine (Jn 15) depicted in red, the colour of divine love, expressed in the passion of Christ. From the cross also streams the life-giving water with deer drinking from it on each side (Ps 42) at the foot of the cross.

The living vine and flowing streams theme then continues in the three windows on each side of the church. The lines grow and flow with the colours gradually changing from an earthly green at the entry end to the heavenly gold in the sanctuary. As the water flows the fishes (symbol of the Christian in the waters of baptism) swim towards the sanctuary, reinforcing the axial way of the church, the path taken by the spiritual aspirant in approaching the Cross of Christ who is the True Vine.

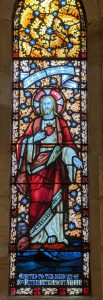

The first two nave windows near the sanctuary were in place prior to Paddy’s contribution; the Sacred Heart on the south side, the Virgin Mary, Star of the Sea, on the north. As noted by Fr Fowler in his book on the history of St Bede’s, these two windows were originally installed in the Chapel at the Catholic Institute for Seamen, Kent Street Sydney, and were moved to St Bede’s in 1983 when the chapel was sold and converted to other uses. The windows were made in the Sydney studio of John Ashwin and Company in 1937. Both appropriately have water depicted at the bottom and leaf motifs at the top. These provided the basis for the water and leaf motifs Paddy used to tie all the windows together.

One hundred and fifty years after this humble little church was built, it was dedicated by Archbishop Anthony Fisher OP on the 10th September 2017. In his closing remarks, the archbishop emphasised the connection between this place and the Saint Bede by reciting the five line poem Bede wrote on his death bed in 734 AD.

One hundred and fifty years after this humble little church was built, it was dedicated by Archbishop Anthony Fisher OP on the 10th September 2017. In his closing remarks, the archbishop emphasised the connection between this place and the Saint Bede by reciting the five line poem Bede wrote on his death bed in 734 AD.

Before setting forth on that inevitable journey,

none is wiser than the man who considers —

before his soul departs hence —

what good or evil he has done,

and what judgement his soul will receive.

That the ‘inevitable journey’ from the earthly realm to the heavenly is marked here in St Bede’s Pyrmont by Paddy Robinson’s windows which employ the same medium used by the glaziers of St Bede’s monastery in the 7th century. They are a source of some awe and wonder.

HARRY STEPHENS, architect, taught interior architecture at the University of New South Wales for 40 years. His special interest is the design of sacred space.

Photos of the windows and Paddy Robinson by the author.