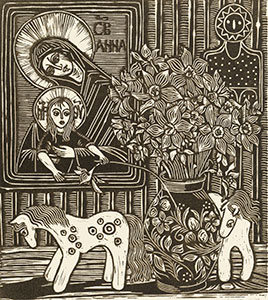

When first saw this piece in the early 90s, I was also exploring the Catholic faith. The imagery of an icon was immediately recognisable and arresting. The simplicity of rendering in apparent monotone and the animation of the child I found appealing. It represented for me a gentle welcome into a faith community that has since become my spiritual home. It also became a vehicle for a line of enquiry into my place in the Church and that of women in general.

Called Natasha, it is a work by Australian artist G.W.Bot. From her early oeuvre, she created it in 1988 when she was an artist in residence at Studio One, Canberra. A limited-edition print, it was made from one linocut block in black and gold ink on paper. It is a relatively large piece and thus has ‘presence’ and clearly significant as evidenced by its place in the National Gallery of Australia collection.

On first appearances it seemed to be what we are most familiar with in icons: Mary holding the baby Jesus. But on closer inspection we can see that the child is a girl. As someone from occidental Christianity, this appeared radical in perhaps suggesting a feminine aspect of Christ. I have since discovered that Bot is an orthodox Christian of the Russian tradition in which icons are an integral part of worship and everyday life. That the piece is inscribed with the word “Anna” meant that in fact this was an icon of Saint Anna holding her daughter Mary, mother of Our Lord.

Upon discovering Natasha in a Studio One exhibition I knew I had to own it. Perhaps it was the delightful way that the child reaches out for a flower, or the fact that it was actually a girl that caught my imagination at the time! Certainly, as an artist myself, called to create works in the religious genre, I regard art as an important vehicle for prayer and this piece appeared to be one that I would find nourishing. It not only gave me pause for reflection, but was to be material for exploring my calling as a Woman of Faith.

Bot says of this piece “In this image, St Anna is myself, holding my daughter, Natasha, who playfully reaches out from the icon to pick a spring daffodil from the Russian vase on the table while the folk horses circle it as in a paddock circling a tree. In other words, an icon connects us in our daily lives to the Godhead – we are all a sacrifice not just the Christ child – we are born and we will die – a universal image about this life and its mysteries.”

This statement is at once informative and inspiring. I have come to understand not only who is represented but the significance of the subjects to the artist as both Woman and Mother. She has taken the liberty to use an image from the most traditional of artistic practices (Icons) and interpolated her own experience of faith. As a mother myself, this is something to which I can easily relate. Her claim “an icon connects us in our daily lives to the Godhead – we are all a sacrifice not just the Christ child …” in my view gets to the nub of the matter.

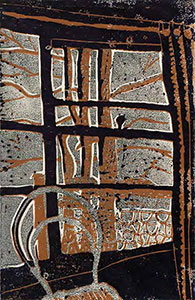

The mystery of the icon and, in particular the metaphor of Mother and Child, has been a profound basis for her artistic practice. An icon is, as it were, a window into the numinous. In reading a catalogue for a 30-year survey of Bot’s work The Long Paddock, I discovered how the artist has stepped into and beyond this window. The earliest work discussed in this catalogue, Window (1981), reveals signs of the beginning of this journey. The catalogue author, Peter Haynes, refers to “window as a motif” and reflects on its meaning to German Romantic Caspar David Friedrich (1774 – 1840). “The highly symbolic language found in Friedrich’s art saw his using the interior as signifying the present, earthly life, while the deliberately contrasting, light-filled world outside the window was an ideal to be reached.” In Natasha we see evidence of Bot’s earthly, everyday life with elements of her domestic setting (horses, the vase and the Kimberley ‘icon’) and by contrast, she enters into the “ideal to be reached” by stepping through this window into the holy figure of St Anna and with her, her daughter Natasha into that of Mary.

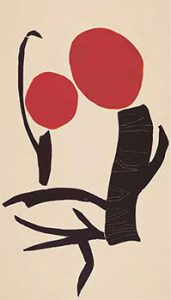

Bot not only refined the Mother and Child theme, but in stepping through the window and into nature, she takes the observer on a meditative journey and teaches us a new and liberating language through marks she refers to as “glyphs”. In Australglyph deciphered, mother and child (2006) we can observe the heads of mother and child, while their bodies and limbs are like tree trunks and branches, described with the interplay glyphs. Of an earlier work Field of glyphs (2004), Hayes says “the artist extends her vision of landscape by adopting the position of meditative observer looking both into herself and apprehending nature in all its mysterious intensity” (p17). By moving beyond the literal of Natasha, though to greater abstraction with the language of her glyphs, Bot liberates us to move beyond traditional imagery, which in a religious context may, for some, be constraining, to the wide field of our imaginations and apprehending the Godhead in all His/Her mysterious intensity.

There is much discussion at present about the role of women in the Church. To me, Bot very boldly side-steps this issue and goes to the very heart of faith itself. To be sure, we are reminded of the central role of women as progenitor of new life and nurturers through the Mother and Child imagery in Natasha and other works in this theme, but through her art, we are also taken from the space we occupy in our everyday lives through the window of her art to the “ideal to be reached”, which in my mind is a personal encounter with the Godhead. In fact, we become one with God and it does not matter what gender we are. I am reminded of the time-tested statements “we are the Body of Christ” and “Christ lives in us and we live in Christ.” which suggests the truth of this perspective.

Indeed, as Tina Beattie, professor of Catholic studies at Roehampton University has said “to say that women image Mary and men image Christ, and to suggest that women cannot say ‘This is my body’ is to exclude the female flesh from the body of Christ.” She goes on to say that we must affirm in women the “dignity, equality and freedom that Christ offers to all who are made in the image of God and incorporated by Baptism into His body beyond all divisions of gender, race and class (see Galatians 3:26).” [1]

It has been the voice of those in the Church, who share such views, that have led me to find in it a spiritual home. It is a voice that calls all and welcomes all. It is a voice not constrained by tradition, but works with it to present a theology to which we can relate in our “daily lives”. As a work that I’m privileged to own and see every day in my home, Natasha, in particular, assures me of my place in our Church and more broadly offers a sense of hope for us all.

Irene Sutherland

February 2020

[1] “A ‘frozen’ idea of the feminine”, The Tablet, February 20, 2020

List of works (in order of appearance)

Natasha (1988)

Linocut, printed in black and gold ink, from one block paper Impression 10/16

Printed image 61.5 h x 55.2 w cm

Sheet 80. h x 60.3 w cm

Collection of the author (reproduced here is the edition in the National Gallery of Australia collection)

Window (1981)

Linocut on photographic paper

30 x 23cm

Private collection

Australglyph deciphered, mother and child (2006)

Linocut on Magnani paper 92 x 52cm

Private collection

Field of Glyphs (2004)

Oil on Belgian linen 81 x 158cm

Private collection