As a refugee from political suppression in his native Hungary, in 1949 a young architect escaped by making his way through the snows of the European winter camouflaged in a white sheet. After a long and arduous journey, he eventually arrived in Australia where he was to become one of the most influential identities in Australian architecture.

As a refugee from political suppression in his native Hungary, in 1949 a young architect escaped by making his way through the snows of the European winter camouflaged in a white sheet. After a long and arduous journey, he eventually arrived in Australia where he was to become one of the most influential identities in Australian architecture.

L. Peter Kollar, Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of NSW, acclaimed by generations of students as the most challenging thinker and teacher of architecture, died 20 years ago after 40 years dedicated to his art. His teachings were based on timeless principles setting him apart from the mainstream and providing a powerful basis for the critical appraisal of the plethora of architectural movements that ebbed and flowed around him.

Amongst his papers he left this short statement:

I am an artist. I don’t work to live – I live to work. I wish my life to be a work of art. I work to make artfully – to make works of art. My art should endeavour to shine a new light on the wonder of the world and the human condition in all its complexity – so that I enliven those who meet my work with the same sense of joy and wonder I see in the world. No work of art deserves to be so called if it is exclusive, self-referential. – LPK

His art was as both an accomplished practitioner and a teacher. Gaining 1st place in the Australian entries and 4th place overall in the international competition for the Sydney Opera House, placed him in company with some of the finest architects in the world, however, when he saw Jorn Utzon’s entry he recognised the genius Utzon was and became one of his most vocal supporters. In the turmoil that followed the NSW government’s dismissal of Utzon from the Opera House project, the local architectural profession was split into opposing camps and Kollar’s championing of Utzon did little to help his academic career. Nevertheless, his teaching, based on his prolific writings on architecture, the great Spiritual Traditions of the world and on the principles and theory of design, was profoundly influential.

His art was as both an accomplished practitioner and a teacher. Gaining 1st place in the Australian entries and 4th place overall in the international competition for the Sydney Opera House, placed him in company with some of the finest architects in the world, however, when he saw Jorn Utzon’s entry he recognised the genius Utzon was and became one of his most vocal supporters. In the turmoil that followed the NSW government’s dismissal of Utzon from the Opera House project, the local architectural profession was split into opposing camps and Kollar’s championing of Utzon did little to help his academic career. Nevertheless, his teaching, based on his prolific writings on architecture, the great Spiritual Traditions of the world and on the principles and theory of design, was profoundly influential.

Everything he did and taught was informed and guided by a deep commitment to his Catholic faith. Some time after the Opera House competition, he experienced what he confided to his closest friends was a metanoia that led him to test his vocation with the contemplative Carthusian monks of San Bruno in Italy. After a time there, his spiritual director discerned that his true vocation was in teaching. He returned to Australia focusing on understanding and communicating the perennial principles evidenced in the Divine Creation and imitated in the sacred arts of Tradition. He became for his students the gatekeeper to an order of knowledge that was intensely spiritual and solidly grounded in the knowledge of these Traditions. In a rare honour the University of NSW was formally congratulated by the international assessors of his Doctoral thesis on Symbolism in Christian Architecture. It was proclaimed the greatest work of its kind. Fellow architect and devoted friend, Paul Walsh, eulogist at Professor Kollar’s Requiem Mass, spoke of a man whose personal, academic and public life were based to the end on an heroic love of God. “His life and his teaching” said Walsh “gave witness to his belief that in the words of St John, ‘you will come to know the Truth and the Truth will set you free’”.

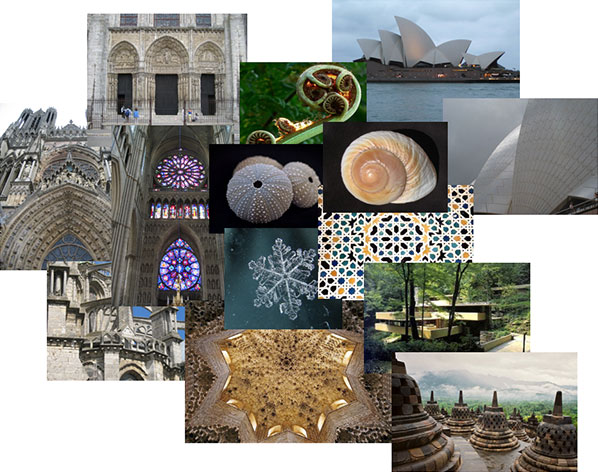

He taught that architecture, if it is to serve us well, must address the whole human condition, accommodating our physical needs superbly, providing excellent food for our minds but above all addressing our need for spiritual nourishment and inspiration in all aspects of our lives. In the preface to his book Patterns of Delightful Architecture he wrote “ ….art, which includes architecture, is at its best when it serves the entire human destiny, of which our earthly life is only a part, – a mysterious, wondrous, beautiful reflection of a total destiny vastly transcending all spatial and temporal limitations.”

Observing the worldwide superficial and confused state of architectural practice and discourse he sought a renewal of the art of architecture by focussing on a thorough understanding of the principles that must underpin every architectural endeavour. “The renewal we seek is neither a revolution nor an evolution. It is to be approached by eliminating, clearing away, the accumulated error of decades and centuries; not by adding some hitherto unknown elements to the architectural vocabulary, but by focusing our attention on its innermost core. We need a renewed attitude of mind which centres itself on the inexhaustible, causal pattern: on the intelligible, not the sensible, on principles not applications.”

This focus on the intelligible instead of the sensible and on principles instead of applications runs directly counter to the vast majority of current thought and practice in architecture and when well understood, is sadly but truly revolutionary.

In the introduction to his most erudite and arguably most influential work entitled Form he wrote “A true intellectual understanding of form as a principle of manifestation is without much hope unless a universal exposition of manifestation as a whole is attempted, leading far beyond the physical world known to our senses and by our reasoning based on sensory data. However, this ‘beyond the physical’, or to use the Greek term, this metaphysical realm, cannot be seen either by our bodily eye, or by the eye of our rational mind. To gain a glimpse of metaphysical knowledge the opening of a third eye is required; the opening of our intellectual eye, which sadly remains closed and asleep for most of our generation.”

This was his constant theme – the imperative that we learn to open our intellectual eye, the ‘eye of the heart’, that God-given faculty of the human condition that enables us immediately to see the Truth and that artists and architects have an obligation to assist others to do the same.

This was his constant theme – the imperative that we learn to open our intellectual eye, the ‘eye of the heart’, that God-given faculty of the human condition that enables us immediately to see the Truth and that artists and architects have an obligation to assist others to do the same.

The full potential of the means of correcting the malaise that Kollar saw in architectural theory and practice set out so clearly in Patterns of Delightful Architecture can be best appreciated when seen in conjunction with the material he presents in Form wherein he offers a means of comprehending and working in harmony with the order that permeates existence. The perception and appreciation of the pairs of ‘antinomical qualities of form’ that he encourages are crucial to this. Continuity and alternation; dependence and authority; completeness and transformation, and many other pairs of such qualities that are to be observed in all that exists, when well understood, can inform the making of the most meaningful architecture. The continuity that runs through the great building holding its many parts together is never at the mercy of or without the attentive company of her partner, alternation. Together they sing of complex harmonies that bring joy to the heart and allow us an insight into the unifying order of existence. The authority of the great building in whole and in part is dependent upon its connection to the complex socio-spatio-temporal continuum which brings it into existence, and which allows its continued existence. In its wholeness, the great building gives unequivocal expression to the quality of completeness without ever disavowing transformation – whilst embracing permanence, it will facilitate and resonate in harmony with the ever-changing patterns of life within and around it.

One of Kollar’s most well attended series of lectures was on The Spirit in Architecture wherein he demonstrated how an understanding of the theory of Form and the perennial principles of architecture is able to give meaning of the highest order to every creative act and most particularly to the making of great architecture. He taught that Beauty (understood as the attractive power of Truth) is to be sought in all we do and that “..to participate in Beauty any creature or any work of art has to speak about something immeasurably greater than itself, something precious, something incomprehensibly important and speak with lucidity and clarity. It has to speak about Truth by the Spirit of Truth, about the wonderful beauty of the Truth”. (Patterns of Delightful Architecture)

It was Beauty to which attention was drawn by me when giving one of three short ‘memorial’ lectures delivered to about one hundred of Kollar’s friends and family members who gathered in his company in the unusual circumstance of a ‘memorial’ whilst the subject being memorialised was still alive. Kollar was dying of cancer and when we discovered this, three of his former students, Michael Tawa, Stan Fung and I, invited him to come with his wife and family and many of his friends to these memorial lectures at the University of NSW. Michael’s talk “On being near and far” was a personal expression of the intellectual journey that he had taken to that point so deeply influenced as it was by Kollar’s teachings. Stan, in talking of the traditional Chinese garden, expressed his gratitude to Kollar for introducing him to a manner of engaging with a subject in which he was passionately interested. My talk “Reflections of Beauty” attempted to do something that Kollar never tired of encouraging – that we seek the Beautiful in everything we encounter.

In thanking us for the most unusual opportunity to be able to attend his own memorial gathering, Peter most graciously, if altogether inaccurately, said “And thus the student surpasses the master”.

No teacher can ever know the full extent of the effects they have on the minds and lives of those they teach but there can be no doubt that even now, twenty years after his death, Kollar remains the most influential teacher of architecture that we have had in Australia.

Harry Stephens