The Art of William Robinson

The Art of William Robinson

Standing awestruck before a mountain, [the mystic] cannot separate this experience from God, and perceives that the interior awe being lived has to be entrusted to the Lord. “Mountains have heights and they are plentiful, vast, beautiful, graceful, bright and fragrant. These mountains are what my Beloved is to me. Lonely valleys are quiet, pleasant, cool, shady and flowing with fresh water; in the variety of their groves and in the sweet song of the birds, they afford abundant recreation and delight to the senses, and in their solitude and silence, they refresh us and give rest. These valleys are what my Beloved is to me.”

Pope Francis, Laudato Si’, 234; quoting John of the Cross, Cantico Espiritual, XIV, 6-7.

Pope Francis goes on to explain how the sacraments are a privileged way in which nature is taken up by God to become a means of participating in the eternal. It is in the Eucharist that all that has been created finds its greatest exaltation, he says. The Eucharist joins heaven and earth; it embraces and penetrates all creation (236).

The creation paintings of William Robinson are the perfect expression of these insights. The new art gallery on the Gold Coast in Queensland (Home of the Arts HOTA) reunited his seven monumental creation works for the first time in its inaugural exhibition entitled Lyrical Landscapes (31 July-17 October 2021). Monumental they are: varying in height from 1.5 to 2 metres, they are between 5 and 8 metres long; they were painted over a sixteen year period (1988-2004).

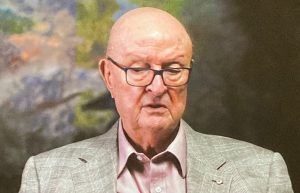

In 1984, Robinson (b. 1936) had moved with his wife Shirley and the family to a farm at Beechmont in the Gold Coast hinterland. His walks in the Lamington National Park immersed him in the surrounding eucalyptus and rain forests and transformed his painting. He returned periodically to painting the farm with its hens and goats and, more recently when bushwalks were no longer possible, he has produced intense smaller-scale domestic still-lifes; but his visionary landscapes remain the core of his oeuvre.

In 1984, Robinson (b. 1936) had moved with his wife Shirley and the family to a farm at Beechmont in the Gold Coast hinterland. His walks in the Lamington National Park immersed him in the surrounding eucalyptus and rain forests and transformed his painting. He returned periodically to painting the farm with its hens and goats and, more recently when bushwalks were no longer possible, he has produced intense smaller-scale domestic still-lifes; but his visionary landscapes remain the core of his oeuvre.

As he walked among the gnarled trunks of ancient trees and followed the path of mountain streams, he would look up into the branches and see the sky, he would look down the cliffs and ravines and see the mighty trees from above, he would catch glimpses of the vista that opened across the valleys and the Pacific Ocean. For both him and the viewer, it is an immersive experience – he once compared himself to a bird flying through the landscape. He realised that another dimension was required to paint these enchanting and dizzying surroundings.

As he worked on his pictures from memory in his studio, Robinson’s unifying vision comes from within, and is expressed on canvas by combining various viewpoints and perspectives. It seems strange at first. Trees grow downwards from the top of the picture or sideways from a cliff. But then we realise that when we look upwards, the tree behind us appears from the top of our field of vision. Robinson’s global vision of the entire landscape is thus able to transcend what any camera captures and encompasses a faith-filled revelation of God’s creation.

Speaking of ancient 2000-year-old trees, Robinson said, I could sense a connection with eternity through them. And you realise how little you know and have to accept about the unknown in creation… a search for spirituality is something that happens when you can move outside of yourself and you are carried into a space that belongs not to geography but a space that belongs outside of it; and once you reach that sort of point, you can make a connection with eternity, spirituality and with God. (Video, Lyrical Landscapes)

I have always loved Monet’s ability in his water lily paintings to capture several dimensions simultaneously: you see the water lily on the surface of the water, the mysterious depths below the water, and the reflections of sky and willow above the water. Such a multivalent perception is captured well by William Robinson. In the forest mist, water reveals its inner depths while at the same time reflecting the moon or the stars of the night sky. The dank intimacy of a forest path explodes into the infinite light of the dawn; night and day move across the landscape. Truly, Robinson’s landscapes, arising from a deeply held Catholic faith, are a majestic encounter with the transcendent.

A few weeks after contemplating the exhibition Lyrical Landscapes, I was able to spend several days myself walking in the forests around Beechmont. The paintings helped me to see the landscape; the landscape helped me to see the paintings. It has been a profoundly spiritual experience of wonder and awe before the Creator God.

A few weeks after contemplating the exhibition Lyrical Landscapes, I was able to spend several days myself walking in the forests around Beechmont. The paintings helped me to see the landscape; the landscape helped me to see the paintings. It has been a profoundly spiritual experience of wonder and awe before the Creator God.

Our Eucharistic Prayers at Mass frequently pick up the exaltation of the Creator in the creation. We pray: You are indeed Holy, O Lord, and all you have created rightly gives you praise… (EP III); Existing before all ages and abiding for all eternity… the source of life, [you] have made all that is, so that you might fill your creatures with blessings… We too confess your name in exaltation, giving voice to every creature under heaven, as we acclaim: Holy Holy Holy…. (EP IV). What we proclaim here with our voices, William Robinson has said in paint.

Rev Dr Tom ELICH is Director of Liturgy Brisbane and chairs the National Liturgical Architecture and Art Council.

For further reading, see the exhibition catalogue which includes magnificent fold-out reproductions and an essay on the relation of Robinson’s painting with his love of music. Lyrical Landscapes: The Art of William Robinson (HOTA, 2021).