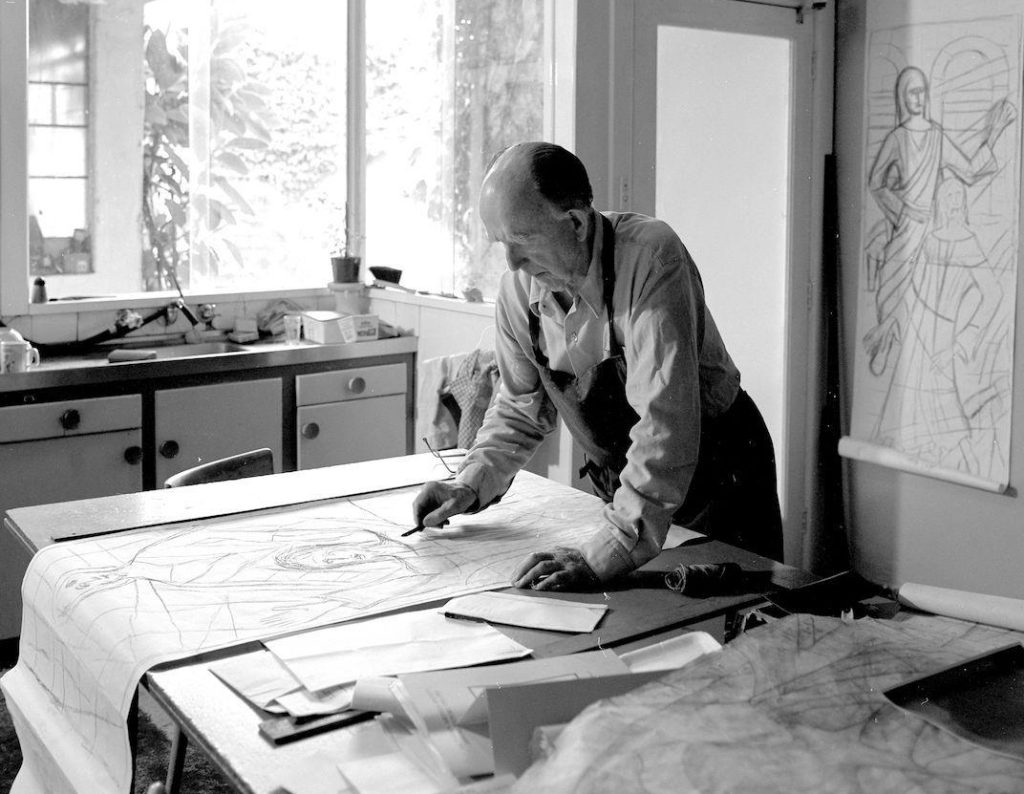

Alan Sumner mbe (1911-1994) was a painter, printmaker, teacher and stained-glass designer. After studying at the NGV school, RMIT and the George Bell School in the early 1930s, Sumner travelled to Europe and the UK, furthering his training at the Grand Chaumière and the Courtauld Institute. Returning to Melbourne, he took up an apprenticeship as a stained-glass designer with Brooks Robinson before becoming a designer for Yenckens. He taught painting at the NGV school from 1947 to 1950 and spent nine years as Head of School from 1953 onward. Meanwhile, over the course of his career he completed approximately 100 commissions for windows in Melbourne and internationally. (National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, 2018).

Alan Sumner mbe (1911-1994) was a painter, printmaker, teacher and stained-glass designer. After studying at the NGV school, RMIT and the George Bell School in the early 1930s, Sumner travelled to Europe and the UK, furthering his training at the Grand Chaumière and the Courtauld Institute. Returning to Melbourne, he took up an apprenticeship as a stained-glass designer with Brooks Robinson before becoming a designer for Yenckens. He taught painting at the NGV school from 1947 to 1950 and spent nine years as Head of School from 1953 onward. Meanwhile, over the course of his career he completed approximately 100 commissions for windows in Melbourne and internationally. (National Portrait Gallery, Canberra, 2018).

Stained glass is an architectural art with a long tradition. In the period after World War II, waves of migration supported burgeoning suburbs around Australia’s major cities. The 1950s also saw the growth of cream brick parish churches. Sumner was sought out by architects designing these new churches, for example, Alan Robertson, Stan Moran, and Edward Billson. Commissions varied from singular works (often World War II memorials) to window programs occupying whole walls.

Sumner developed designs for St Francis Xavier Church, Frankston, that responded to Robertson’s 1954 Modernist design: ‘Redemption’, based on a simple cross and the symbols of Christ’s passion, filled the west wall, while a similarly large window in the shallow transept depicted the patron saint of the church with a stylised map of his travels.

In 1956, Robertson engaged Sumner for similarly large windows and a series of small door panels for a new church at Mordialloc. As well as the patron saint, St Bridget, and Our Lady, Patroness of Australia, Sumner designed a memorial to the men of the 58/59 battalion of the Australian Army who had died in the battles against the Japanese in New Guinea.

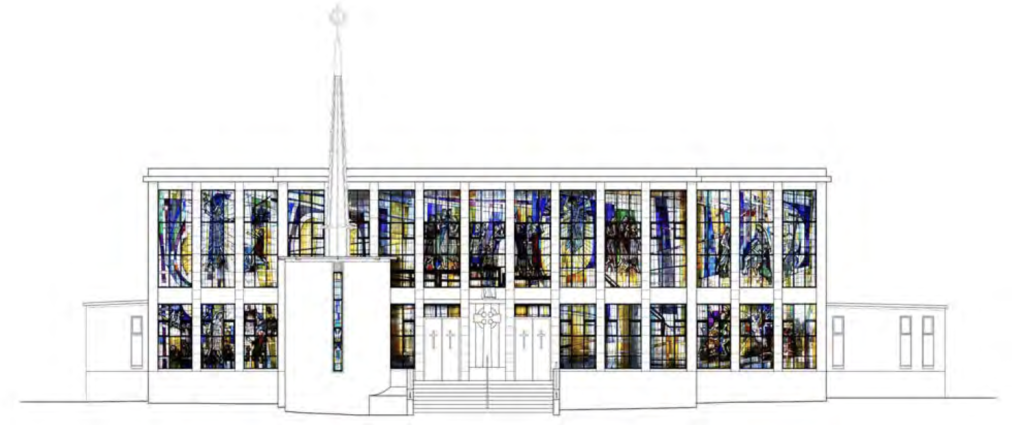

Stained glass was a major element of St Oliver Plunkett Church, Pascoe Vale, another Alan Robertson church design, completed in 1961 and filled with Sumner’s glass over the next four years. Scenes from the Life of Christ, the Deposition, Resurrection and Ascension float within the huge expanse of the ‘west’ wall (170 square metres) and allow for a light-filled interior to the building. A further wall of stained glass in the sanctuary depicts Christ on the cross. Bronwyn Hughes (1977) describes these windows as Sumner’s most important cycle, comprising the largest continuous area of stained glass in the southern hemisphere.

Elizabeth Richardson (2017) argues that the narrative purpose of the windows and the clear figuration of characters is a quotation of the way a traditional domus ecclesia communicates and articulates meaning. Yet, modern churches in Europe of the 20th century, such as the Catholic churches of Notre-Dame du Raincy, Paris, France by August Perret (1923); ‘Steel Church’, Essen, West Germany by Otto Bartning (1928, destroyed 1943); and St Maria Königin, Cologne, Germany by Dominikus Böhm (1952-54), were already moving toward the use of abstract stained glass in their new thinking about an appropriate modern aesthetic expression in ecclesiastic architecture.

Alan Sumner only fully discovered the potential of Modernism for stained glass during a visit to Europe in the early 1950s. His visits to major Gothic cathedrals were balanced by his study of the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, and, more significantly, the works of El Greco which would bring a new impetus to his stained-glass designs (Hughes 2012). This influence is particularly evident in his elongated figures, with their expressive elegant hands. The backgrounds recall the geometric abstract patterning of contemporary artists Leonard French, Leonard Crawford and Roger Kemp. As Bernard Smith (1991) writes space is either non-existent or shallow; the totality of the surface pattern from edge to edge is an important factor of the design; colours are strong, resonant and unmodulated, and a cloisonné binding line enhances and divides colour areas. Sumner’s skill in integrating naturalistic figures within his beautiful mastery of abstract design is palpable.

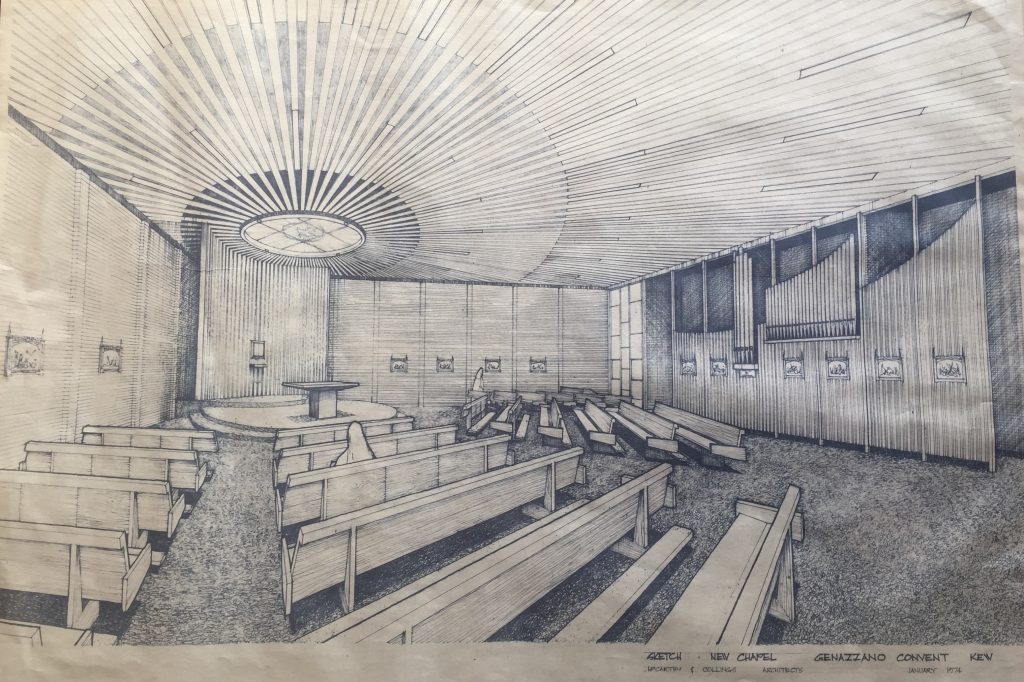

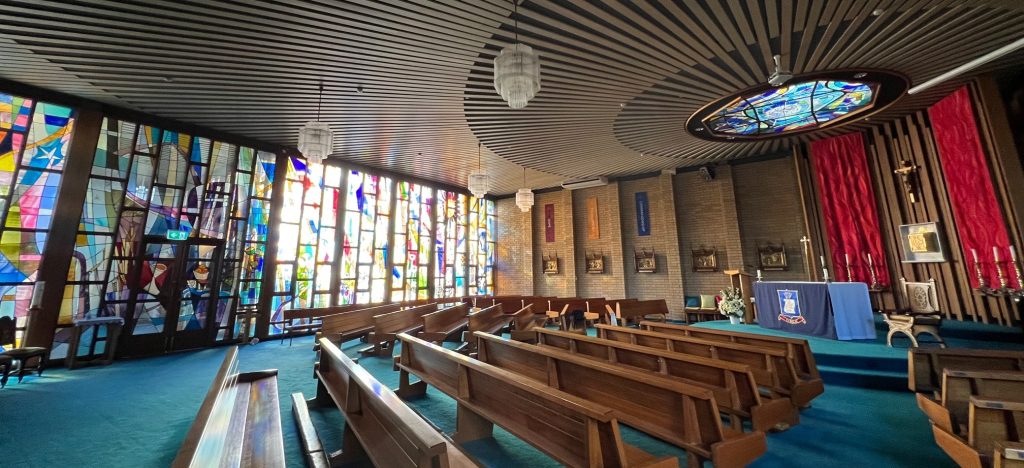

On a smaller scale, McCarthy and Collings’ design for the Genazzano Convent Chapel, Kew, 1974, (above) is complemented by Sumner’s glass program. The Holy Spirit is above the sanctuary and provides top lighting (left); the seven gifts (wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord) are incorporated into an entire wall of the chapel (below). The scheme is particularly appropriate for the College which the chapel serves.

On a smaller scale, McCarthy and Collings’ design for the Genazzano Convent Chapel, Kew, 1974, (above) is complemented by Sumner’s glass program. The Holy Spirit is above the sanctuary and provides top lighting (left); the seven gifts (wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety, and fear of the Lord) are incorporated into an entire wall of the chapel (below). The scheme is particularly appropriate for the College which the chapel serves.

Few churches could afford to install an entire cycle of windows in their newly completed buildings. Sumner’s windows accommodated tight post-war budgets by filling large expanses of his glass walls with a majority of commercial glass. He only used expensive ‘antique’ glass for focal points and important subjects and was judicious in his use of glass paint and silver stain. Sumner, with the encouragement of his architect and clergy commissioners, often prepared scale drawings for entire cycles of windows, knowing that only a small proportion would be commissioned immediately. In some instances, the process continued for twenty or thirty years.

Chapel Genazzano College, Kew. Details showing various techniques of texturing, staining and painting, interspersed with commercial glass.

At St Cecilia’s, South Camberwell, the first commissions occurred in the 1960s. When a new church was commissioned and built in the early 1970s, it incorporated all the Sumner windows from the old church. For example, the new Lady Chapel is framed by the Annunciation and the Nativity. There is a Pope Pius X window which side lights the sanctuary. In the narthex are windows showing St John Vianney and Christ’s charge to St Peter. Drawings for these three windows are among the State Library of Victoria’s collection of 800 Sumner drawings.

St Cecilia’s Church, South Camberwell, Victoria. Left to right: Annunciation, Nativity, Charge to St Peter.

Here, in these examples, we see the fruition of Sumner’s study of life drawing in George Bell’s school, combined with the study of composition and colour harmonies. Sumner considered art to be about form, design, harmony, rhythm and balance (The Australian, 3 December 1986). Design is all important, but it is only when it is coupled with meticulous craftsmanship and extraordinary energy that it results in the creation of significant aesthetic form.

Sumner remarked that My work is about anticipation, the next step, the stillness between what is to happen next … it is about people just waiting (The Age, 17 September 1990).

Architectural historian, Dr Ursula de Jong, is Honorary Associate Professor in the School of Architecture and Built Environment at Deakin University, Geelong.

REFERENCES

Photo of Alan Sumner (1993) by Francis Reiss (© Estate of Francis Reiss). National Portrait Gallery, gelatin silver photograph on paper (www.portrait.gov.au/portraits/2004.34/alan-sumner).

Photo of St Francis Xavier, Frankston: https://www.churchhistories.net.au/church-catalog/frankston-vic-saint-francis-xavier-catholic

St Oliver Plunkett Church, Pascoe Vale

Bronwyn Hughes (1997), “Twentieth century stained glass in Melbourne churches”, University of Melbourne, Masters Thesis, p.103.

Elizabeth Richardson (2017), “Negotiating Modernism: How church designs of the post-war era negotiated Modernism in an attempt to renew their image and relevance within an increasingly secular society”, Society of Architectural Historians Australia and New Zealand (SAHANZ), Annual Conference Proceedings, p. 615. Illustration: S Dewhurst, R Fan, M Park, University of Melbourne.

Bronwyn Hughes (2012), “The Art of Light: a survey of stained glass in Victoria”, La Trobe Journal 90, pp. 78-98.

Bernard Smith (1991), Australian Painting, 1788-1990, OUP, p.381.

Chapel, Genazzano College, Kew. Architect’s drawing: Holy Trinity Parish (Bentleigh, East Bentleigh, Moorabbin). Photos: Ursula de Jong, July 2022.

Jane Clark, Alan Sumner, retrospective exhibition, NGV, 1993/1994.