The traditional art of making an icon is an exacting process requiring much skill and knowledge that can only be acquired over a long period of dedicated commitment to the art. The method that aligns best with the essence of the icon is classical painting with egg tempera, a technique of unknown origins from deep within the ancient world. Adopted and perfected by the icon painters of the early church in Byzantium, the technique has been passed down almost without change to be employed by the few icon painters in our age whose practice remains true to the tradition.

The traditional art of making an icon is an exacting process requiring much skill and knowledge that can only be acquired over a long period of dedicated commitment to the art. The method that aligns best with the essence of the icon is classical painting with egg tempera, a technique of unknown origins from deep within the ancient world. Adopted and perfected by the icon painters of the early church in Byzantium, the technique has been passed down almost without change to be employed by the few icon painters in our age whose practice remains true to the tradition.

One such practitioner of the art is Michael Galovic. Born in Belgrade in 1949 and educated at the Belgrade Academy of Applied Arts, he was drawn to icon painting early in his education. By the time he arrived in Australia in 1990 he had travelled widely and experienced much that positively influenced his thinking and his practice. His prodigious output of icons painted in the traditional manner continues at an impressive rate today.

As one might expect of an artist who has dedicated most of his life to this art, Michael is deeply committed to the essential two-way communication between the icon and the viewer. The icon is not just a religious painting: it is sacramental and plays a sacramental role in the lives of those who venerate it.

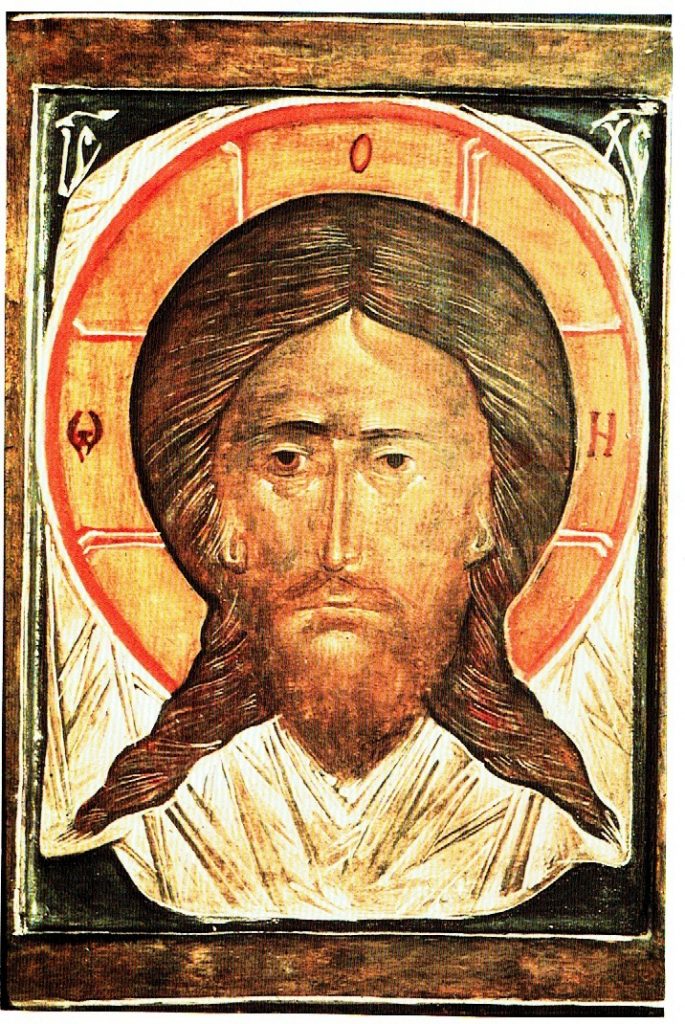

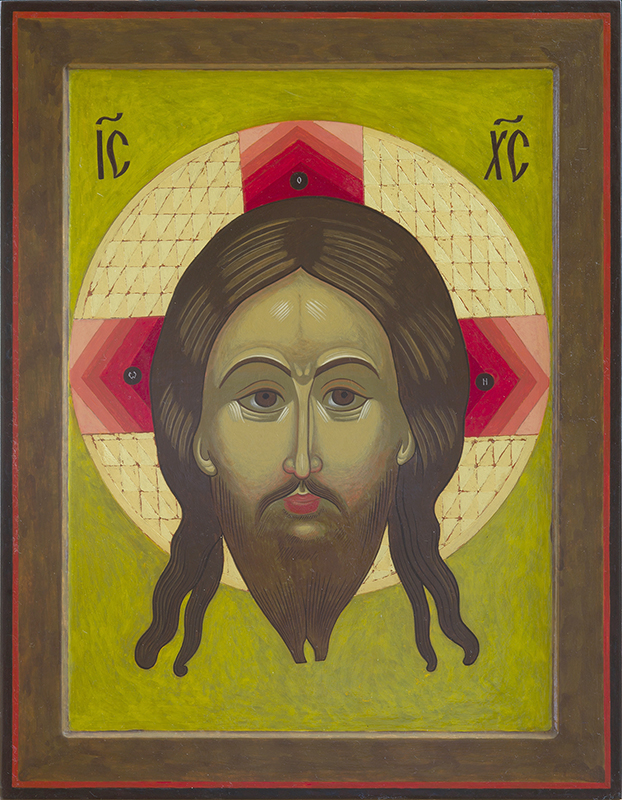

The currently much-abused word icon means ‘image’ whilst in the art of iconography it is the vera icon the ‘true image’ which is its ultimate expression. Tradition maintains that the vera icon is just that, a true image of the sacred personage, accurate in every way.

Both the Latin and the Byzantine churches have venerated the vera icon of the face of the Saviour and the Virgin and Child almost from the outset. Known in the West as the Holy Visage, the face of the Saviour is said to have been received by Veronica (an anagram of ‘vera icon’) miraculously imprinted on the towel with which she wiped his face as he carried the cross to Golgotha.

In the East it has another legendary origin and is called the ‘Saviour Made Without Hands’ (that is, miraculously imprinted). It is known in English-speaking orthodoxy as the Mandilion (from a Greek word for ‘towel’).

The Church had a clear understanding of the significance and the possibilities of the image from its earliest days and this has never really changed. In fact it cannot really change as it is derived from the central tenet of the faith, the divine incarnation, God made man, a revelation not only of the Word but also of the Image of God (Jn 1:14). Just as every effort is made to ensure that the word is carefully transmitted from age to age unchanged, the tradition insists that the Image be a faithful reflection of its sacred prototype.

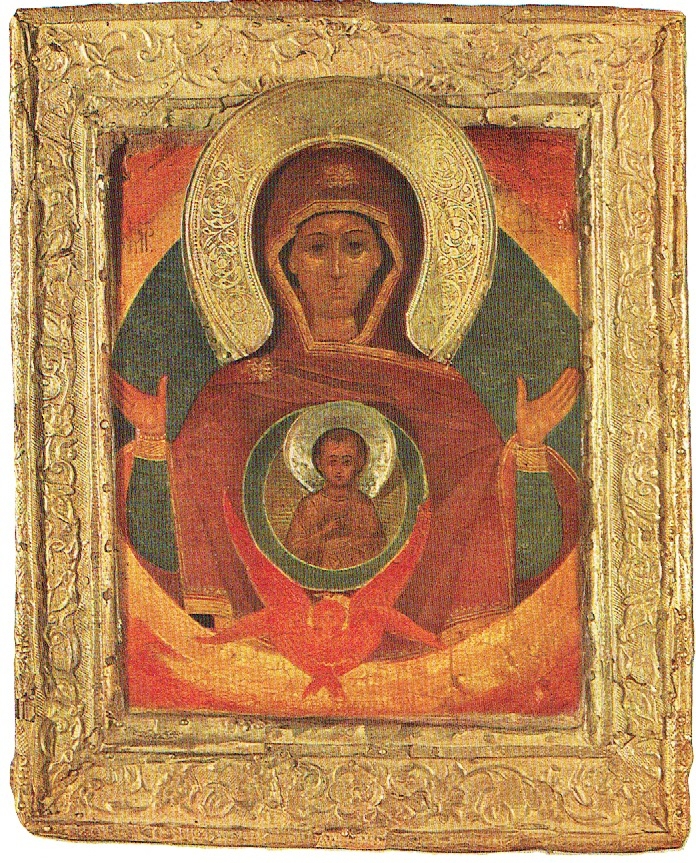

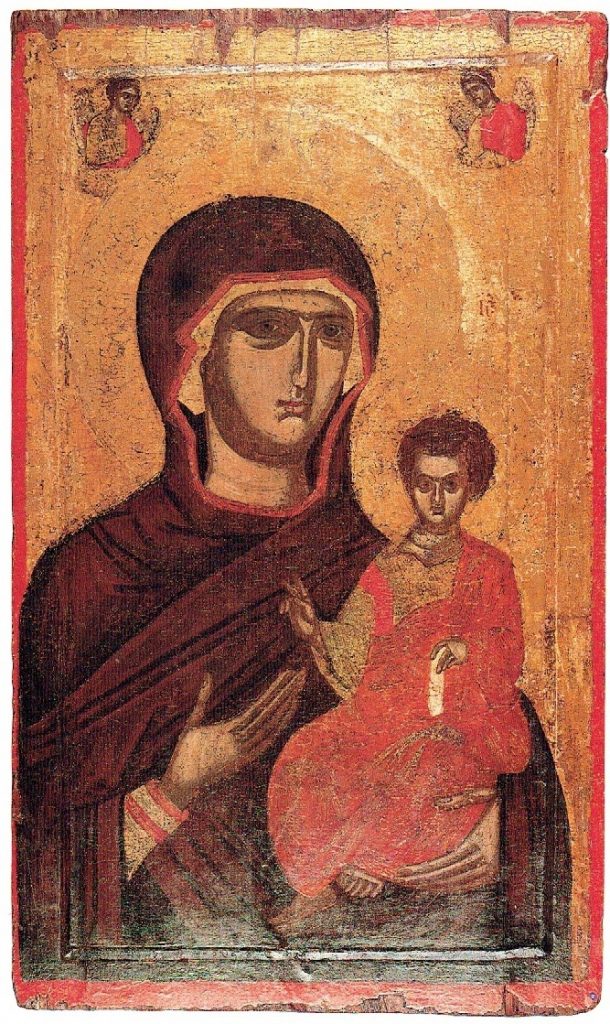

Of the many icons depicting the virgin and child, the Virgin of the Sign is possibly the oldest; depictions of a similar kind have been found on the base of sacred vessels used in the catacombs in the first centuries of the Church. She appears in these icons with arms outstretched in prayer; in her bosom, mostly within a mandorla, is the Christ child for the virgin is both understood in salvation history and fittingly venerated as the mother of God.

Another icon of the virgin and child is the type referred to as the Hodigitria the prototype of which, according to legend, was painted by St Luke and blessed by the Virgin herself.

In this image, widely used in East and West, Mary presents the Christ child and gestures towards him as the source of salvation.

In the daily life of the Eastern Church, the icon is understood to be not merely an optional support to the devotions of the faithful but an essential aspect of the ritual of the faith. In the words of Leonid Ouspensky the icon is both the way and the means; it is prayer itself. (The Meaning Of Icons, p. 40).

The ultimate truths of the faith are eternal. The mission with which we are charged at our baptism is to find ways to reveal these truths in our world in our time. To be effective in this mission, artists seek the ‘heavenly archetypes’ and allow them to speak with clarity through the ‘prototypes’ and ‘stereotypes’ that we fashion. In all that we make and do, but most emphatically in the making of sacred art that is to be of service to the Church’s mission, we must eschew pretentious self-referential novelty.

Our works of art must speak with the authority of the infinite and the eternal in the language of our particular place and time.

Therefore the artist does not just imitate past stereotypes, but prayerfully meditates on the signs of the times in order that the work of art have a true fit to the here and now. This context is not only the obvious and measurable physical environment, but also more so the subtle and spiritual conditions of the time and place.

Michael Galovic recently painted an icon of Mary Help of Christians for the Sydney parish of Rosebery. In correspondence with the parish, he offered the following short explanation of its symbolism. The colour symbolism is as per Tradition in icons. Mary’s inner robe is of the colour blue, standing for her human nature and the outer, red mantle tells us about her being the Mother of God. With the infant Jesus, the colour symbolism is reverse: the inner robe alludes to his divine nature, while the blue/grey one on top, to his human nature, thus satisfying the theological representation of dualism of Christ’s nature. With his right hand he is blessing the world, while the other one holds a scroll with the divine message. His halo is cruciform and the inscription Mary Help of Christians on the icon are there as per Tradition. The Virgin Mary is our help in good times and bad. So the icon shows the virgin and child both against the turbulent waves and the dark blue stillness of quiet waters.

True to tradition, the icon painters of the early Church …drew their creative joy, not from inventing pretentious novelties, but from a loving recreation of the revealed prototypes, whence came a spiritual and artistic perfection such as no individual genius could ever attain. (F Schuon, Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, 1956, p. 36). Michael Galovic sits within this tradition. He recently completed a project that he began many years ago. The evolution of this beautiful Annunciation can be explored in the following clip. https://youtu.be/6gp4yhX7sOY

HARRY STEPHENS, architect, taught interior architecture at the University of New South Wales for 40 years. His special interest is the design of sacred space.

Reference

Ouspensky, L and Lossky, V, The Meaning of Icons (Boston, 1952).