Melbourne architect GREGORY BURGESS (b. 1945) is known internationally for public architecture which both expresses the spiritual and creates a unifying communal experience. His work has included arts and visitor centres, educational and health facilities.

Melbourne architect GREGORY BURGESS (b. 1945) is known internationally for public architecture which both expresses the spiritual and creates a unifying communal experience. His work has included arts and visitor centres, educational and health facilities.

In 1987, he designed the Catholic Church of St Michael and St John in Horsham, a rural city 300 km north-west of Melbourne; it won the Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Architecture Medal that year. It is a fine example of how Catholic Church architecture had evolved 35 years ago. Peter Downton’s words from the jury report are instructive and beautiful in the way they honour this humble country parish church.

We dwell, Martin Heidegger tells us, ‘between earth and sky’. Louis Kahn saw architecture existing at the threshold between Silence and Light. These are expressions of enduring verities. The new Catholic Church for the Parish of St Michael and St John embraces such timeless concepts and transcends issues of transitory fashion. It is, in the words of Greg Burgess, ‘… a modest, but enthusiastic and loving work created by an unusually co-operative team of parishioners, artists, tradesmen, engineers and architects’.

We dwell, Martin Heidegger tells us, ‘between earth and sky’. Louis Kahn saw architecture existing at the threshold between Silence and Light. These are expressions of enduring verities. The new Catholic Church for the Parish of St Michael and St John embraces such timeless concepts and transcends issues of transitory fashion. It is, in the words of Greg Burgess, ‘… a modest, but enthusiastic and loving work created by an unusually co-operative team of parishioners, artists, tradesmen, engineers and architects’.

The building sits in a broad civic zone on the flat open land of Horsham, held by the street grid under the rural Victorian sky. It grows in dark bricks from the earth, curving, reaching up, questing for

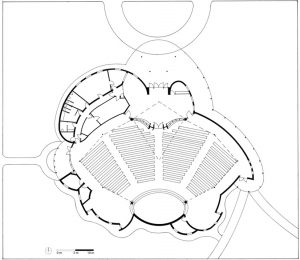

The building sits in a broad civic zone on the flat open land of Horsham, held by the street grid under the rural Victorian sky. It grows in dark bricks from the earth, curving, reaching up, questing for  this sky and lightening as it ascends. Growing from the wide sheltering veranda, the roof planes mirror the distant hills. The whole culminates in a glass cross held within a circle high in the wall behind and above the sanctuary. The building invites all to enter; the walls shepherd a visitor from any direction toward the entries, then encircle and protect. Within, the narthex begins an axial way down the central aisle of the broad nave to the steps of the sanctuary. Above, the ceiling hovers as if held by the glowing light reflected from the warm brickwork. Although the main internal space is broadly symmetrical, other spaces generate the complex curvilinear plan shape.

this sky and lightening as it ascends. Growing from the wide sheltering veranda, the roof planes mirror the distant hills. The whole culminates in a glass cross held within a circle high in the wall behind and above the sanctuary. The building invites all to enter; the walls shepherd a visitor from any direction toward the entries, then encircle and protect. Within, the narthex begins an axial way down the central aisle of the broad nave to the steps of the sanctuary. Above, the ceiling hovers as if held by the glowing light reflected from the warm brickwork. Although the main internal space is broadly symmetrical, other spaces generate the complex curvilinear plan shape.

This is a building concerned with ‘bringing together’. It brings together the skills of the parishioners, the designers and the craftsmen. It is an exceptional testament to their skills, for it is powerfully conceived and exquisitely constructed in every detail down to the purpose-designed sanctuary furniture. Each week, it brings together people from a far-flung parish. It is a magnet and a focus. And, it brings together a complex of forms and symbols into a unified, joyous and tranquil creation intended to ‘…express and celebrate the human being’s journey toward wholeness’.

From a liturgical perspective, St Michael and St John’s represents a distinctive new approach to church design following the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), namely the ‘fan-shaped’ architectural form, which aims to foster the ‘full, conscious and active participation’ of all the people. Three decades on, the vibrant, open space for the assembly, unencumbered by pillars and marked by generous aisles to foster

From a liturgical perspective, St Michael and St John’s represents a distinctive new approach to church design following the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), namely the ‘fan-shaped’ architectural form, which aims to foster the ‘full, conscious and active participation’ of all the people. Three decades on, the vibrant, open space for the assembly, unencumbered by pillars and marked by generous aisles to foster  processional movements, still promotes clear visibility of the liturgical actions at the lectern, altar and presider’s chair.

processional movements, still promotes clear visibility of the liturgical actions at the lectern, altar and presider’s chair.

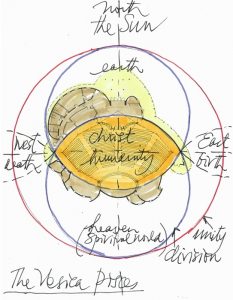

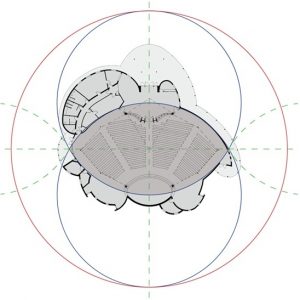

A powerful sacred geometry determines the organisation of the space. The key is the vesica pisces, the lozenge shape created when two equal  circles intersect, with the centre of each lying on the circumference of the other. As Gregory Burgess’ diagram shows, this symbolises the meeting of heaven and earth, made incarnate in Christ. It asserts that the liturgical assembly is the Body of Christ, and its worship is the offering of Christ on the cross which reconciles the world to God. Note how the sanctuary is included within the vesica pisces unifying the whole assembly in Christ.

circles intersect, with the centre of each lying on the circumference of the other. As Gregory Burgess’ diagram shows, this symbolises the meeting of heaven and earth, made incarnate in Christ. It asserts that the liturgical assembly is the Body of Christ, and its worship is the offering of Christ on the cross which reconciles the world to God. Note how the sanctuary is included within the vesica pisces unifying the whole assembly in Christ.

In his doctoral thesis The Architecture of Liturgy: Liturgical Ordering in Church Design (2011), Rev Dr Stephen Hackett judges that the church of St Michael and St John represents a high-point among churches designed with this liturgical ordering. The primacy of the liturgy is apparent in its design, interpreted initially in the symbolism that has been incorporated into its architecture, and then in the ordering of its interconnected spaces (p. 341).

To the east of the sanctuary is a chapel for the tabernacle and, near it, a space for the font; to the west is a curved space for the music ministry. The narthex and entry areas continue the rhythm of the embracing curved walls. The sanctuary, adjacent alcove chapel and music ministry spaces, and reconciliation chapels project from the southern side of the vesica into the circle which represents heaven. The narthex, vesting sacristy and other service rooms extend from the northern side of the vesica into the circle which represents earth (p. 330).

Fan-arrayed churches, Hackett notes, often have a sanctuary set on a level platform that is elevated three or four steps. These sanctuary spaces sometimes resemble a stage, subtly evoking an expectation of performance rather than participation. The sanctuary of St Michael and St John avoids such resemblance through the design of its curving apsidal wall, rose window, and canopy (p. 340).

Fan-arrayed churches, Hackett notes, often have a sanctuary set on a level platform that is elevated three or four steps. These sanctuary spaces sometimes resemble a stage, subtly evoking an expectation of performance rather than participation. The sanctuary of St Michael and St John avoids such resemblance through the design of its curving apsidal wall, rose window, and canopy (p. 340).

The fabric of the church reinforces the sacred geometry to evoke the saving mystery which is celebrated in the liturgy itself. A distinctive  feature of the church is the patterning of its brickwork… In the interior walls, a progressive lightening of colour and shade as the courses ascend is a metaphor for the paschal mystery. Here the brickwork pattern evokes a sense of darkness giving way to light, and of death giving way to life (p. 330).

feature of the church is the patterning of its brickwork… In the interior walls, a progressive lightening of colour and shade as the courses ascend is a metaphor for the paschal mystery. Here the brickwork pattern evokes a sense of darkness giving way to light, and of death giving way to life (p. 330).

The broad suspended canopy hovers over and marks the sanctuary space. In Catholic tradition, covering the altar with a baldachin, ciborium or tester fulfilled the liturgical function of symbolising the Holy Spirit who is prayerfully invoked during the Eucharistic liturgy… In the church of St Michael and St John, the canopy is spread in two curved wings across the whole sanctuary… In its winged design, reminiscent of Scriptural dove imagery, and in the light it mediates, the canopy is a clear evocation of the Holy Spirit (p. 338).

The sacred geometry underlying this building, the materials and design of its fabric and furnishing, and the human experience of being together in this space, all witness to the Paschal Mystery of Jesus’ death and resurrection and work together to make of the human liturgical act a participation in the things of heaven.