The Australian sculptor, Thomas Dwyer Bass am, was born in Lithgow in 1916. After various jobs during the Depression and army service during WWII, he began his career as a sculptor on graduating from the National Art School in 1948. Prior to the war, Bass attended Dattilo Rubbo’s art school; it was here he was initiated into the principles of art. At the National Art School he came under the influence of Lyndon Dadswell whose assistant he became during 1949-1950. This was followed by a three-year stint of teaching there. From 1951-1964 he held various executive positions with the Sculptors’ Society, of which he was a founding member.

The Australian sculptor, Thomas Dwyer Bass am, was born in Lithgow in 1916. After various jobs during the Depression and army service during WWII, he began his career as a sculptor on graduating from the National Art School in 1948. Prior to the war, Bass attended Dattilo Rubbo’s art school; it was here he was initiated into the principles of art. At the National Art School he came under the influence of Lyndon Dadswell whose assistant he became during 1949-1950. This was followed by a three-year stint of teaching there. From 1951-1964 he held various executive positions with the Sculptors’ Society, of which he was a founding member.

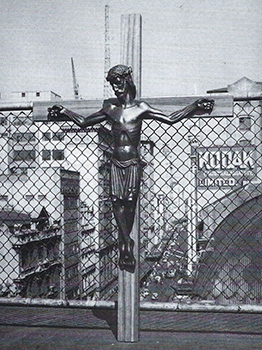

While teaching at the National Art School, an architect came in search of someone to sculpt a crucifix for the chapel of the newly built Jesuit Theology College at Pymble. Tom ‘grabbed’ the opportunity! Thus began the church work of one of Australia’s eminent sculptors.

In 1996 Bass, aged 80, co-authored a book with Harris Smart Tom Bass Totem Maker. It is from this book I have chosen five works that have become significant symbols for the communities who commissioned them between 1955 and 1967. The images are accompanied by Tom Bass’s own reflections on the genesis, meaning and development of each work.

![]()

My upbringing had been Anglican and the Catholic Church seemed like a foreign, strange, almost heathen thing. The crucifix was like a ‘graven image’. But my sculptural instincts won through and I accepted the commission.

My upbringing had been Anglican and the Catholic Church seemed like a foreign, strange, almost heathen thing. The crucifix was like a ‘graven image’. But my sculptural instincts won through and I accepted the commission.

In a way it is a strange crucifix. It is not like the usual ones where you see this desperate, pathetic sort of figure hanging on the cross. This Christ looks almost as if he in in the act of ascending off the cross. He is not a victim. But rather is freely offering himself as a sacrifice.

The crucifix was so successful that the same architects commissioned me to do sculptures for the new church being built for the Catholic Archbishop of Canberra-Goulburn at Yass.

In 1953 the architects took me to Yass to meet the bishop, Dr Guilford Young. It was an extraordinary meeting of minds. Our origins, our education and our lives could not have been more different. He was a Roman bishop, I a Protestant layman. He had trained as a priest, been schooled in Rome, become a Doctor of Divinity, while I was a married man with four children, almost entirely self-educated – a product of the Depression years and of a life which had been chaotic and insecure.

In 1953 the architects took me to Yass to meet the bishop, Dr Guilford Young. It was an extraordinary meeting of minds. Our origins, our education and our lives could not have been more different. He was a Roman bishop, I a Protestant layman. He had trained as a priest, been schooled in Rome, become a Doctor of Divinity, while I was a married man with four children, almost entirely self-educated – a product of the Depression years and of a life which had been chaotic and insecure.

Despite all these differences – or was it because of them? – our minds met like two sparks. Guilford Young gave me the sense of meaning that I’d been searching for. We’d come from opposite ends of the world, but we’d reached the same point. He’d realised that his theology needed to be expressed in formal terms made visible, and I’d realised my sculpture needed to be filled with his theology.

The crucifix on the front of the church [at Yass] was to be a symbol of suffering, because this church is also a memorial for the Second World War, a remembrance to the sacrifice of those who died in that war. We chose to represent the moment in the crucifixion when Christ says, My God, my God, why have you forsaken me? That moment of anguish and desolation felt to me like a moment that the men and women who’d been through the experience of the war could readily identify with. This crucifix became an emblem for modern humanity in the hydrogen bomb era – frightened and bewildered at the results of their own clever godlessness. I felt instantly that all this could be expressed by that strange, apparently paradoxical moment in the Passion.

I also did a seated figure of St Paul for inside the church [St Augustine’s, Yass], portraying him as a sailmaker, which was his trade, but full of mystical power. Almost every feature of the sculpture is symbolic and expresses an aspect of his life, work and spirit.

The shining wrinkled brow expresses his divine anxiety. What he called his ‘anxious care’. The eyes express the deep mystic soul of the man and I wanted the mouth to be one that would say, ‘Though I speak with the tongues of men and angels and have not love I am become as sounding brass or a tinkling cymbal.’ The nose expresses his powerful leadership. The hands are those of a workingman, but also sensitive, sacramental. The feet are those of a missionary, a traveller who tramped the lengths and breadth of the known world. The needle he holds is the symbol of Paul himself, sharp, penetrating and creative. The sail he is stitching is the theology of Christianity. The folds of the sail as they break over his arm make the architectural form of a church. Paul was a remarkable man, Greek-born, a Roman citizen, a Jew and a Christian all at the same time.

At one point Guilford Young had suggested that the loosely falling thread of St Paul’s needle should assume the Greek letters for ‘In Christ’, but it came out looking too clever, as if he had just performed a conjuring trick. I got over it by incising the letters into the sail and encircling them with thread.

I felt very close to Paul while doing that sculpture. He seemed to manage things himself, only requiring my co-operation. I used to get a message from him every morning before leaving the house at 7.15a.m. Just at that time on the radio a priest would read from his epistles. The whole family thought and talked about St Paul.

Soon after I’d begun the period of instruction [to be received into the Catholic church] I was asked by Father Roger Pryke if I would make a font for his church in Camperdown. In preparation for my own baptism I was considering what baptism really signified, so the font came to embody all those things which were happening in my life at that point.

Soon after I’d begun the period of instruction [to be received into the Catholic church] I was asked by Father Roger Pryke if I would make a font for his church in Camperdown. In preparation for my own baptism I was considering what baptism really signified, so the font came to embody all those things which were happening in my life at that point.

The idea of baptism, as I came to understand it was originally an immersion, a symbolic death. So the base of the font that I made has seven portals in it, which stand for the seven deadly sins. After the immersion, one is symbolically buried in the tomb with these seven deadly sins. Out of the tomb of sin rises the resurrection column which supports the font.

The font itself represents the waters of baptism, and swimming in it is the crucified Christ in the form of a fish stabbed by a cross. With its circular structure the font cover represents the universal church. It had twelve portals for the twelve apostles and they stood for the twelve broad categories of people for whom the Church provides an entry. The sculpture as a whole expresses the death and resurrection process: the immersion is the death, followed by the descent into the tomb of sin, then the resurrection through the waters of baptism into the Church.

Working for the St Vincent de Paul Society was a very special part of my experience as a Catholic… The aim of the Society is to follow Christ’s injunction: To give a cup of water in my name is to give unto Me. I used to go to an insignificant little chapter of the Society at Ingleburn, between Liverpool and Campbelltown, with a group of really hard-working, humble working-class Catholic laymen. The president was a bloke named Terry Grace. He didn’t have that name by accident. He was a wonderful, unpretentious man and he really did have grace about him.

We had our duties. We’d go out and visit families who were in trouble. There were those living in tents along the river, fringe-dwellers around the village, people who’d gotten into trouble through booze. They were all known and there was a regular visiting pattern.

Terry had got wind that the Society wanted a logo and he asked me if I’d take it on. The design consists of three hands and a cup. One hand is reaching out with the cup, another is receiving it, and the third – the one with the wound – is Christ’s hand blessing the transaction. It’s now used worldwide, even in unexpected places like Turkey.

I regard this as one of the really important things I’ve done. It began very simply, from participating with those few laymen. It’s like a memorial to that time in my life and to my having belonged to that group.

![]()

CHURCH WORK OF TOM BASS

1953 Crucifix, Canisius College Pymble NSW

1954 St Joseph the Carpenter, St Mary’s Church Warren NSW

1955-56 External Crucifix, St Augustine’s Church Yass NSW

1955-56 Reredos Crucifix, St Augustine’s Church Yass NSW

1955-56 St Paul the Sailmaker, St Augustine’s Church Yass NSW

1955 Saint Francis Xavier, St Francis Xavier’s Church Ashbury NSW

1959 St Ignatius, St Ignatius College Riverview NSW

1958-60 Edmund Rice, St Patrick’s College Goulburn NSW

1958-60 Baptismal Font, St Joseph’s Church Camperdown NSW

1960-61 High Altar, Saint Mary’s Cathedral Hobart TAS

1959-62 Our Lady Archetype of the Church, Saint Mary’s Cathedral Hobart TAS

1961 Sacred Heart, Sancta Sophia College University of Sydney NSW

1964 Saint Luke Ikon, St Vincent’s Hospital Darlinghurst NSW

1965-66 Crucifix, Royal Military College Duntroon ACT

1966 Votive Figure, St Aloysius College Adelaide SA

1967 St Vincent the Paul Logo

1969 Sculptured Altar, St Vincent de Paul Church Redfern NSW

1969 Our Lady and Christ the Priest, St Patrick’s Seminary Manly NSW

1969 Wall Sculpture, Poor Clare Monastery Campbelltown NSW

1984 Mary Immaculate, Mary Immaculate Church Bossley Park NSW

1987 Our Lady of Sorrows, Cannosian Hospital Oxley QLD

1987 Magdalene Foundress, Cannosian Hospital Oxley QLD

1987 Saint Paul, Aurora College Moss Vale NSW

1995 Reredos Cross, St. Finbar’s Church Glenbrook NSW

1997 St Peter Julian Eymard, St Francis Church Melbourne VIC

2004 St Augustine, St Augustine’s Church Yass NSW

Early in his long life, Tom Bass espoused the idea that sculpture ‘had a totemic function in society; through sculpture, people, communities and societies have been reminded of the things that are most important to them’. This idea came to rich fruition in the 1950s when he discovered that in the Catholic church he had found a community of people who needed the totemic forms he could make – ‘forms that would symbolically convey the values and meanings that were of real significance to them’. This he did for fifty years. Tom died at the age of 93 on 26 February 2010.

Presented and edited by Jill O’Brien sgs

All quotations from Tom Bass: Totem Maker, Tom Bass and Harris Smart (Australian Scholarly Publishing, 1996).

Marco and Tim Bass and Margo Hoekstra-Bass generously offered advice for this article.