How did the form of Catholicism adopted by the Mparntwe Arrernte people of Alice Springs Australia become what it is today? Catholicism was introduced by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC) and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart (OLSH) from 1935, but the image of modern Catholicism practised by Mparntwe Arrernte Catholics varies in significant ways from what they were taught in the mission.

How did the form of Catholicism adopted by the Mparntwe Arrernte people of Alice Springs Australia become what it is today? Catholicism was introduced by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart (MSC) and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart (OLSH) from 1935, but the image of modern Catholicism practised by Mparntwe Arrernte Catholics varies in significant ways from what they were taught in the mission.

The meeting at Manaus of the Amazon River with its main tributary the Rio Negro, named because of its distinctively black water, presents a metaphor for the relationship between the two imaginaries Altyerre and the Cosmic Christ. When the rivers meet, they do not mix, but run parallel for six kilometres, maintaining their own character, because they move at different speeds, with different temperatures and different water density. Eventually they coalesce, mingling the life inherent in each, forming the Amazon, which supports more abundant life in its flood plain before flowing into the Atlantic Ocean. They can do this because they are both constituted of water, a fundamental requirement for life on our planet.

This image conjures the coalescence of the ancient Arrernte imaginary called Altyerre and the Judaeo-Christian imaginary inculcated by the missionaries. Each is constituted of a network of beliefs and practices, or imaginary, and at first sight the two imaginaries are quite distinct and cannot mingle. Yet they have come together. Each imaginary, I would argue, enhances the other.

Earlier this year, some members of the Catholic Church at the Synod of Bishops on the Amazon in Rome threw an Amazonian indigenous icon of a pregnant indigenous woman and other icons into the Tiber River. They severely criticised the Pope and his supporters for condoning the inclusion of pagan images within the Church, and issued a public statement: ‘It is our duty to follow the words of God like our holy Mother did. There is no second way of salvation. Christus vincit, Christus regnat, Christus imperat. (Christ conquers, Christ rules, Christ governs all.)’

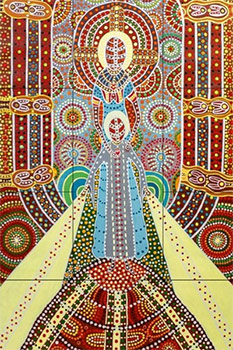

My image of the combining of the Rio Negro and the Amazon would clearly not be accepted by these extremist Catholics. But Pope Francis is right to honour the prior religious practises of the Amazonians, just as the Bishop of Darwin is supportive of a process that since 1935 in Central Australia has seen the development of Altyerre-Catholicism. Amazingly, almost on the same day the Amazonian Madonna was being thrown into the Tiber, in Alice Springs a remarkable stained-glass window painted by Arrernte artist Kathleen Kemarre Wallace was unveiled in the OLSH church.

The window represents an ancient Greek Icon of Mother and Child. The wonder of the symbolic form of the window is that it reflects the coalescence of the two streams of influence in the modern Mparntwe (Alice Springs) Arrernte imaginary — firstly, the continuing stream of ancient Altyerre consciousness of Mparntwe Arrernte Catholics, and secondly, the more contemporary stream of Judaeo-Catholic spirituality that was introduced by the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and the Daughters of our Lady of the Sacred Heart.

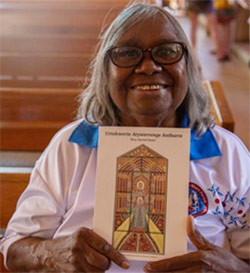

Kathleen Kemarre is a child of both traditions. She is a vibrant repository of the ancient law passed to her from her arrenge/father’s father, atyemeye/mother’s father, her aperle/father’s mother and ipmenhe/mother’s mother, as evidenced in her book Listen Deeply, Let My Stories In. But as well she is a child of the dormitory at Ltyentye Apurte/Santa Teresa, where she learnt the foundations of 1950s and 60s Catholicism from the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart.

You do not need to be Arrernte to appreciate the symbolic story expressed in it — although it helps.

The painting is a sacred rendition of themes that belong to both traditions. This is certainly an Arrernte painting and expresses an Arrernte perspective, but it is no exaggeration to say that many more non-Arrernte will view this art work than will Arrernte. You do not need to be Arrernte to appreciate the symbolic story expressed in it — although it helps. Let me suggest that Arrernte viewers will see it as an image of menhenge atherre/mother and child (son) while non-Arrernte might recognise Madonna and Child.

What are the deeper themes from both traditions that the viewer might alert to? Because the window adorns the Church of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart there is no question that it reflects an image of the beating heart of both the mother of Jesus and of Jesus himself. This is the core of the spirituality of French priest Jules Chevalier, the founder of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and the Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart.

Perhaps the first thing that the viewer may ponder is the absence of facial details of the two figures. This is not because Kathleen Kemarre is not a skilful artist. Rather it is out of respect. Ikirrentye/respect is a fundamental Arrernte value. Kathleen Kemarre will not attempt to represent the physiognomic features of Mary and Jesus because she feels she could never — even with her consummate skill — do them justice.

But even more fundamentally Arrernte artists do not generally paint faces because faces represent the physicality of a person, not their utnenge/spirit, life. This is why there are warnings at the time of death of a significant person that a photograph of the deceased might appear in a news report. Arrernte know that it is not the body of a person that is important, it is their eternal spirit. To attempt to represent the person of Mary or Jesus would be to overlook their essential essence, their utnenge/spirit.

Kathleen Kemarre may not be aware of the Hebrew scriptures’ concept of rahamin, which translates as womb-compassion, yet she draws the eye of the viewer from the absent faces to the position of the head of the child directly in front of his mother’s womb. While Sister Veronica Lawson, in her book The Blessing of Mercy, points to this allusion as a way of seeing a feminine aspect of the Hebrew idea of ‘God’, it might be that Kathleen Kemarre is more alert to her Arrernte core concept of conception totemism.

Conception totemism describes how a child derives her spirit. When an Arrernte mother becomes aware of her pregnancy, she becomes aware of when and where she conceived. She locates the apmere/country of that event and then deduces that it was from the utnenge/spirit of that apmere/country that the ampe akweke/child in her womb draws its utnenge/spirit. This is one of the ways a child is informed about her spiritual origins. There are others.

The relationship between a child and its arrenge/father’s father or paternal grandfather is one of the most essential in establishing Arrernte identity known as aknganentye, meaning born from or originating in the creation. And the identity derived from mother’s father/atyemeye or maternal grandfather is known as altyerre. So, this window is a rich source of stimulation to Arrernte viewers. It reminds them of who they are in the same way that Wenten Rubuntja’s painting, in the vestibule of the OLSH Church, also does. And Wenten was explicit about aknganentye and altyerre when he offered the painting to Pope John Paul II in November 1986.

Wenten said:’ That’s the country line — the traditional place. Pmere aknganentye, that’s the Dreaming story. A traditional painting from the time when people were rushing to meet the Holy Father from Rome. That’s the Creation story, Dreamtime Aknganentye — Creation of the world… This story comes from the Father of Heaven, who was living in the world here — that’s the place that he is related to through Altyerre (Dreaming) … (The painting) has all those things — body paint and song and all. This is a dancing ground. (The Church) was a dancing ground — now it’s a big temple.’

Like Wenten’s painting, this depiction alludes to the menhenge atherre/mother and son, the altyerre heritage of the child. Jesus is the child of a woman and draws his totem from her father, his atyemeye. This grounds Jesus in the earth. He is like all humans, a child of the universe, made of star stuff as we all are.

The next arresting image of the window is the embrace of the child by his mother. Nestled under her breasts, her arms enfold the child, intent on keeping him safe. This, along with the term menhenge atherre, alerts the viewer to a dominant feature of Arrernte culture, the kinship system/anpernirrentye. In Arrernte culture every single person is held in the web of kinship. There are no escapees. Anpernirrentye/kinship holds all Arrernte in a warm and consoling embrace. When an Arrernte person sees this image, she knows what it means. It means nurture, nourishment, consolation and life.

The Arrernte word for this is arntarntareme/holding/caring. It is such a powerful concept that there are some synonyms for arntarntareme. The Eastern and Central Arrernte to English Dictionary actually says arntarntareme means to look after someone or care for them. Another word is atnyerneme, for which the first example given in the dictionary is to hold a child and rock him to sleep. Another, antirrkweme, is given as ‘holding hands’. What they all express is the human touch that characterises care and concern for the wellbeing of others. Arntarntareme means to reach out and hold, look after, nourish, save and nurture others. It might well be compared to womb compassion/rahamin!

Our gaze is transferred at last to the hands of Jesus. Here, in a symbol more resonant of western art, Kathleen Kemarre has streams of light gushing from Jesus’ hands. Surely the image here is of the arntarntareme/holding, caring, looking after by both Jesus and his mother for the entire world and every person in it. The streaming light image reflects back to traditional Christian images of lifegiving water. The spirituality of the Sacred Heart of Chevalier is based, according to the MSC website, on a text from John’s gospel: ‘Out of the believer’s heart shall flow rivers of living water.’ Adding to the complexity of the images is the knowledge that kwatye/water is a common totem of many Arrernte families.

There is another way of ‘seeing’ the light streaming from the hands of the youthful Jesus. It is worth noting that the Arrernte have adopted the word Ngkarte as a word for what we might call ‘God’. The original meaning of ngkarte was ceremonial leader. Arrernte ceremonies are based around many rituals some of which involve dance. A ngkarte is not a hereditary chief but a periodic leader in sacred ritual. Additionally, ngkartes are also often understood to be anangkeres/healers.

Margaret Kemarre Turner, in her book Iwenhe Tyerrtye: What it means to be an Aboriginal person, provides a glimpse of the work of youthful anangkeres/healers. She says: ‘A grandfather might teach his grandsons to be singers of a special healing song. But the healing comes from our nature, you know, from the Land. That ‘electrolight’ is just from that nature. Also they’re born with it too, and the person who’s got that electrolight nature, he can touch people around him. When that child is born, ‘Hey, that kid’s gonna be this!’ They know it straight away because he’s got that ‘electrolight’ of nature inside him.’

Notice the handing on of power through anpernirrentye from arrenge/grandfather to arrenge/grandson. Margaret Kemarre’s ‘electrolight’ is her way of describing the healing power of the angangkere. Power to love, to forebear, to heal, to survive — all another way of understanding salvation or redemption, or indeed the incarnation — is understood as being provided by light streaming from the child’s hands. It is through Jesus and Mary, ultimately from God, that Kathleen Kemarre might be offering an image of her Ngkarte/God in this painting.

The images just keep on collapsing into each other or coalescing into one all-encompassing and ambitious imaginary that might well be called Altyerre-Catholicism. Every time the congregation in the OLSH Church in Alice Springs sings and dances under the gaze of this exhilarating window the ‘Father of Heaven’ is dancing for joy, and Altyerre lives on in this sacred dancing ground.

Mike Bowden has worked as a teacher and community worker in Alice Springs and Aboriginal communities in the Top End. He received a theology PhD from the University of Divinity in Adelaide in December 2019, for his thesis exploring Aboriginal and Catholic spirituality, ‘Searching Altyerre to Reveal the Cosmic Christ’.

Mike Bowden has worked as a teacher and community worker in Alice Springs and Aboriginal communities in the Top End. He received a theology PhD from the University of Divinity in Adelaide in December 2019, for his thesis exploring Aboriginal and Catholic spirituality, ‘Searching Altyerre to Reveal the Cosmic Christ’.

Article: Reprinted with permission from Eureka Street, 4 December 2019