CLIFTON PUGH (1924-1990) was an Australian landscape and portrait painter. His engagement with the bush, however, stands in sharp contrast to the familiar landscapes of artists such as Arthur Streeton and Frederick McCubbin.

CLIFTON PUGH (1924-1990) was an Australian landscape and portrait painter. His engagement with the bush, however, stands in sharp contrast to the familiar landscapes of artists such as Arthur Streeton and Frederick McCubbin.

He was more influenced by 20th century German Expressionism. In the late 1950s, under the umbrella of a group called ‘The Antipodeans’ (with artists such as Arthur Boyd, John Brack, Robert Dickerson, John Percival and Charles Blackman) Pugh championed figurative painting which addressed Australian cultural identity. While some of his colleagues relocated to London, Pugh built himself a simple dwelling, Dunmoochin, at Cottles Bridge near Melbourne. Here he was able to study the Australian bush ‘up close’ and observe the cycles of death and rebirth. To this end, he also travelled Australia, including several influential trips to the Kimberley where he encountered indigenous art.

Pugh was marked by the horror and violence of fighting in Papua New Guinea in the last years of the War. Although he became a pacifist, a cruel savagery remains evident in his paintings of animals in the harsh Australian bushland. He chose to paint conflict: fighting cocks, the death of a wombat, the aftermath of bushfire, shooting wild dogs, magpies attacking, feral cats… He avoids the grand panorama of scenery to get close to his subjects, engaging with the offensive and the ugly, and finding beauty in angular shapes and strong colours. This was his response to words of the Antipodean Manifesto: Our experience of this life must be our material. We believe that we have both a right and a duty to draw upon our experience both of society and nature in Australia for the materials of our art.

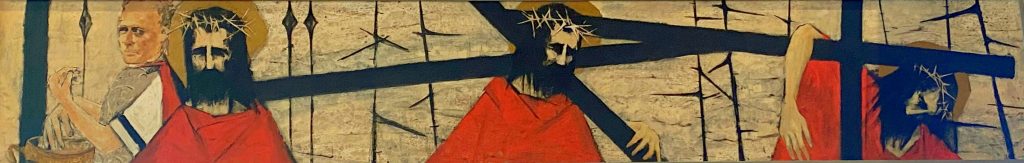

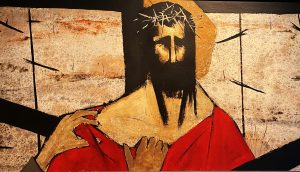

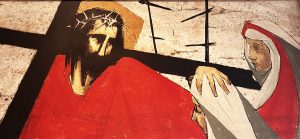

It was a bold but enlightened move on the part of the Catholic community at Eltham to commission Clifton Pugh to paint a set of Stations of the Cross in 1961. The parish had had some exposure to contemporary art – it is located to the north-east of Melbourne, halfway between the artist’s community at Heide and Pugh’s art centre at Cottles Bridge.

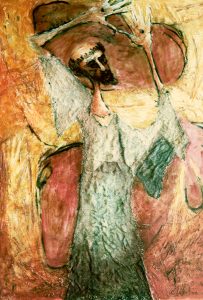

Pugh was able to bring to the work his own suffering as an artist for, to accomplish his artistic work, he had needed to forego physical comfort and overcome considerable criticism and discouragement. In the four panels of the Stations he focusses on the haunting face of Christ who is clothed in a bright red garment. The images are held in a matrix formed by the repeated black cross and set against a rocky background with branches of long thorns.

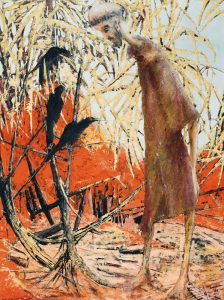

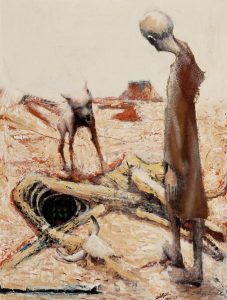

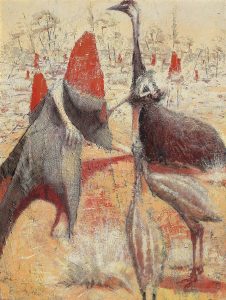

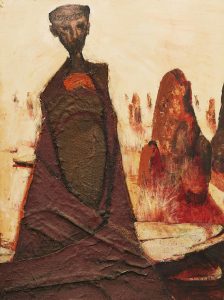

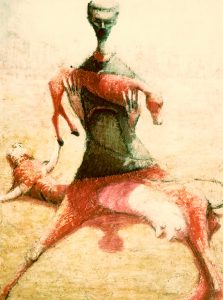

The survival of European settlers in an inhospitable land is the context in which he understood his own struggle and sacrifice for his art. Late in 1964, Pugh took his family to the Kimberley. The eleven paintings done at this time explore the subject of St Francis, depicting the human figure in a rugged landscape. Like Clifton himself, St Francis represents a love of nature and its animals, a commitment to poverty and simplicity of life, and the experience of suffering. St Francis embraced the cross of Christ and bore the wounds of Christ (the stigmata) on his body. One can understand Pugh’s spiritual identification with St Francis.

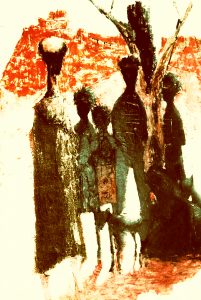

At the time, he wrote to a friend: I’m painting people in the natural environment now, before I only painted animals, quite often in human situations. I have always felt that perhaps humans were a horrible mistake on the part of nature – alien – I was always outside looking in. Up north for the first time I really felt I belonged. I could never feel lonely up there, the rocks, trees and birds were all one with me… To start painting such different feelings I’ve started with St Francis (he had the same sort of feelings)… I am perhaps not so much talking of the life of the Saint but using him to express my feelings (Allen, p. 66).

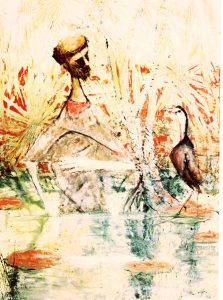

Pugh does, however, take some of the traditional tales of Franciscan legend and transpose them into an arid Australian setting. For example, we have him talking to the birds and taming a dingo (instead of the wolf of Gubbio).

This series is painted in oil on hardboard and incorporate (in a typical 1960’s technique) hessian collage for Francis’ robe. Personal though they may be for Clifton Pugh, there is an important lesson here for all. For inculturation is an imperative if faith and the liturgy are to be integrated with our Australian sensibility and way of life. Clifton gives us a new perspective on evangelical poverty and what it might mean in our part of the world. Taken out of 13th century Italy, St Francis is shown to us in an accessible Australia setting. Pugh’s philosophy and his art also encourage us to appreciate and care for our environment.

images from the St Francis series

After painting the St Francis series, Pugh was able to visit Mexico where he was fascinated by penitents who inflicted pain upon themselves as a discipline. He painted a further series of works out of this experience on the meaning and power of suffering. He once explained suffering for his art in a television interview: And I suppose having those hard times, it’s absolutely instilled in me now that there’s nothing else in the world I will ever do except paint. Now whether that’s necessary, whether that’s a human condition that somehow or other we need some sort of suffering, that I’m not sure about. I certainly know… it strengthens your own discipline and will (Allen, p. 68).

TOM ELICH, Director, Liturgy Brisbane

Acknowledgements: With thanks to the Estate of Clifton Pugh, his sons Dailan Pugh and Shane Pugh, for permission to reproduce the images of Pugh’s work. Thanks to Michael Sierakowski for supplying images of the Stations of the Cross at Our Lady Help of Christians church at Eltham, Vic.

Bibliography: Traudi Allen, Patterns of a Lifetime: Clifton Pugh (Thomas Nelson, 1981)