Victorian sculptor Ernst Fries is known for his monumental works in stainless steel and granite, glass and concrete. He was born in Würzburg, Germany, and after a difficult childhood during World War II, studied gold and silver-smithing in Switzerland. He came to Australia in 1959. He settled in the Yarra Valley in 1986 where the landscape inspired him to explore themes of rebirth and new life in the elegant clean lines of his modern sculpture. With work in gallery collections in Australia and overseas, he has received many commissions for public sculpture, for example, in 2013, the glass and concrete panels of the Yarra Glen Black Saturday Memorial.

Victorian sculptor Ernst Fries is known for his monumental works in stainless steel and granite, glass and concrete. He was born in Würzburg, Germany, and after a difficult childhood during World War II, studied gold and silver-smithing in Switzerland. He came to Australia in 1959. He settled in the Yarra Valley in 1986 where the landscape inspired him to explore themes of rebirth and new life in the elegant clean lines of his modern sculpture. With work in gallery collections in Australia and overseas, he has received many commissions for public sculpture, for example, in 2013, the glass and concrete panels of the Yarra Glen Black Saturday Memorial.

Top left: Yarra Glen Memorial. Right and bottom: St Ita’s Church, Drouin.

Over the last sixty years, Fries has made significant contributions to liturgical art. He contributed to a number of churches using dalle de verre glass set in concrete. A good example is the Easter window at St Ita’s Church in Drouin, a town east of Melbourne in the Diocese of Sale.

Ernst Fries also made sacred vessels and other liturgical objects for the post-Vatican II communion rites. The chalice and paten illustrated here are cast in silver with the textured surfaces expressing the plastic quality of hand-made forms. The silver contrasts with the smooth gold-plated interior and creates a tactile experience as the vessels are handled and the chalice is passed to the communicants. Fries also made matching silver-plated candlesticks and other objects in this style, sometimes for secular use.

Ernst Fries’ sacred vessels.

One of the most interesting examples of his work is the crozier Fries made for Archbishop Frank Little of Melbourne (1974-1996). It shows the crucified Christ with hands detached from the cross and reaching out. The image neatly combines Jesus in his death and resurrection.

Fries was inspired by articulated medieval figures of Christ. These had moveable limbs and head and were used to depict the crucifixion, descent from the cross, burial and resurrection of Christ. The existence of these figures, often amazingly lifelike, stimulated the mystical imagination. It is not uncommon to find stories and illustrations of Christ who descends from the cross to embrace or bless, to point or admonish.

In his Golden Legend (Ch 12), Jacob of Voragine (1230-1298) speaks of the Lord’s Passion and of the crucified Christ drawing to himself all humankind. He quotes Saint Bernard meditating on the crucifix: He has his head inclined to be kissed, the arms stretched to embrace us, his hands pierced to give to us, the side open to love us, the feet fixed with nails for to abide with us, and the body stretched all for to give to us. Mystics are portrayed in just this kind of tactile interaction with Christ.

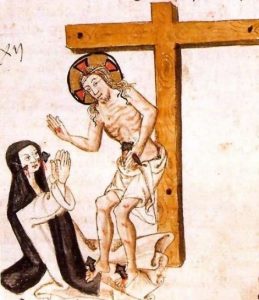

Left: National Library of Spain, Madrid, MS3995 (15th C) fol 37v

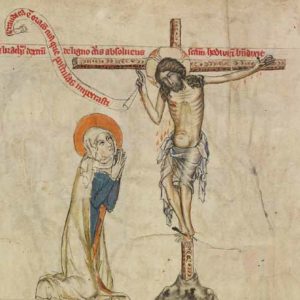

Right: Getty Library, Los Angeles, Hedwig Codex, Ms Ludwig XI 7(1353) fol 24v.

In this tradition, Ernst Fries gives us on Archbishop Little’s crozier an encounter with a living Christ who reaches out to embrace all people from the cross. He is saying that the episcopal leadership symbolised by the crozier manifests the all-embracing compassionate care of the crucified and risen Lord.

Left: Bishop Mark Edwards with the Little Crozier

Bibliography: Medieval references from

John Coman, “No Strings Attached: Emotional Interaction with Animated Sculptures of Crucified Christ”, North Street Review, March 2017.

Jacqueline E Jung, “The Tactile and the Visionary: Notes on the Place of Sculpture in the Medieval Religious Imagination” in Colum Hourihane (ed.), Looking Beyond: Visions, Dreams, and Insights in Medieval Art and History (Princeton: Index of Christian Art, 2010).

TOM ELICH, chair National Liturgical Architecture and Art Council, director Liturgy Brisbane.