The Cathedral of St Stephen in Brisbane holds the best collection of the work of Australian sculptor, John Elliott (1943-2016). Nowhere else are there three major works together. The cathedral has the shrine of Virgin Mary, the altar crucifix and the diocesan shrine of patron St Mary MacKillop. John Elliott was born in Canterbury, England, studied at the Royal College of Art in London, and migrated to Australia in 1970. He taught sculpture at the Queensland College of Art.

The Cathedral of St Stephen in Brisbane holds the best collection of the work of Australian sculptor, John Elliott (1943-2016). Nowhere else are there three major works together. The cathedral has the shrine of Virgin Mary, the altar crucifix and the diocesan shrine of patron St Mary MacKillop. John Elliott was born in Canterbury, England, studied at the Royal College of Art in London, and migrated to Australia in 1970. He taught sculpture at the Queensland College of Art.

Commissioning a work of liturgical art is a collaborative process, because the artist undertakes to place his/her artistic talent and insight at the service of the liturgy and to integrate the work of art with the liturgical space. The artist responds to the Church’s theological/liturgical brief and to the architect’s design brief. The process requires mutual critical reflection throughout the months of executing the artwork. The story of John Elliott’s work at the cathedral will illustrate the process.

The first work Elliott was commissioned to undertake in 1989 was the figure of the Virgin Mary. With help from Michael Putney who taught theology at the seminary and who was later bishop of Townsville, the cathedral team wrote an artist’s brief describing Mary, Woman of Faith. Blessed is she who believed that the promise made her by the Lord would be fulfilled (Lk 1:45). We wanted an image people could identify with, not a remote majestic figure, but a Jewish girl who said ‘yes’ to God and who consequently already carried the Son of God in her womb.

The first work Elliott was commissioned to undertake in 1989 was the figure of the Virgin Mary. With help from Michael Putney who taught theology at the seminary and who was later bishop of Townsville, the cathedral team wrote an artist’s brief describing Mary, Woman of Faith. Blessed is she who believed that the promise made her by the Lord would be fulfilled (Lk 1:45). We wanted an image people could identify with, not a remote majestic figure, but a Jewish girl who said ‘yes’ to God and who consequently already carried the Son of God in her womb.

John Elliott responded by studying madonnas of the renaissance and baroque periods, trying to understand their structure, the flow of lines and the balancing of weight in the figures. He produced dozens of drawings and eventually several maquettes of the Virgin Mary, joyful and graceful, elegant and humble, reflective and spiritual.

Successive meetings of the artist, Archbishop Rush, the architect Robin Gibson, and the liturgical team refined the image. This led to nuancing the relationship between the madonna’s eyes, hands and womb to draw in the worshipper who knelt at the shrine. Elliott used a medieval technique to colour the wooden carving, rubbing back the layers of colour to produce a rich patina on the surfaces.

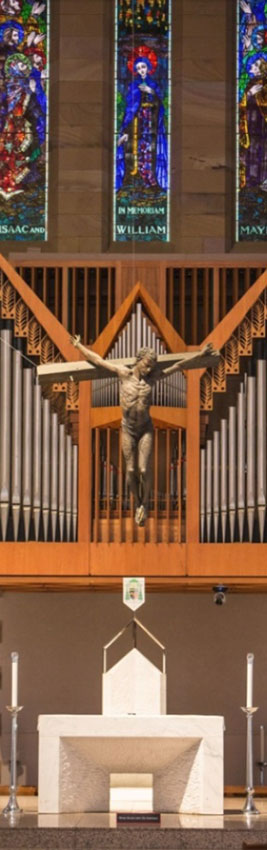

When this work was finished, John Elliott was commissioned to create an altar crucifix. Liturgically, it needed to relate to the altar below it, since the Eucharist is the entry point by which we share in the sacrifice of the cross. Theologically, it needed to encompass the entire Paschal Mystery of Jesus’ death and resurrection (and not a single historical moment in Jesus’ crucifixion). Architecturally, it needed to be conceived ‘in the round’ as the sanctuary is located in the midst of the assembly; this was a particular challenge since the crucifix is traditionally frontal and flat-backed.

When this work was finished, John Elliott was commissioned to create an altar crucifix. Liturgically, it needed to relate to the altar below it, since the Eucharist is the entry point by which we share in the sacrifice of the cross. Theologically, it needed to encompass the entire Paschal Mystery of Jesus’ death and resurrection (and not a single historical moment in Jesus’ crucifixion). Architecturally, it needed to be conceived ‘in the round’ as the sanctuary is located in the midst of the assembly; this was a particular challenge since the crucifix is traditionally frontal and flat-backed.

The process of making multiple drawings and maquettes for consultation began. Elliott worked on the figure of Christ first, shaping the clay from a life model. Scale was an important element in the discernment of the reference group to ensure that the figure would not overpower the altar. The image of a living Christ, resigned in suffering and yet triumphant over death, emerged. Taking his cue from early Christian images of Christ, Elliott portrayed a clean-shaven Christ.

Meanwhile the architect was imagining the pipes of the organ – which would not be installed for another decade – to ensure that all the elements formed an integrated whole. The design of the cross itself was especially fraught. At first artist and architect imagined an outline cross in stainless steel that would serve as a kind of frame for the figure. The team soon saw that it did not work, for the Christ figure became a kind of trapeze artist. Then Elliott suggested including only the crossbeam, the cross disintegrating and rolling away as death yields to resurrection. At once we ‘saw’ the words of Venantius Fortunatus of the sixth century: Life is borne unto death, by death, brought forth into life. After more than a year of discussion and reflection, trial and error, we had arrived at a bold and fitting solution. And, after further decision-making on colouring and patina, the figure was cast in bronze.

Meanwhile the architect was imagining the pipes of the organ – which would not be installed for another decade – to ensure that all the elements formed an integrated whole. The design of the cross itself was especially fraught. At first artist and architect imagined an outline cross in stainless steel that would serve as a kind of frame for the figure. The team soon saw that it did not work, for the Christ figure became a kind of trapeze artist. Then Elliott suggested including only the crossbeam, the cross disintegrating and rolling away as death yields to resurrection. At once we ‘saw’ the words of Venantius Fortunatus of the sixth century: Life is borne unto death, by death, brought forth into life. After more than a year of discussion and reflection, trial and error, we had arrived at a bold and fitting solution. And, after further decision-making on colouring and patina, the figure was cast in bronze.

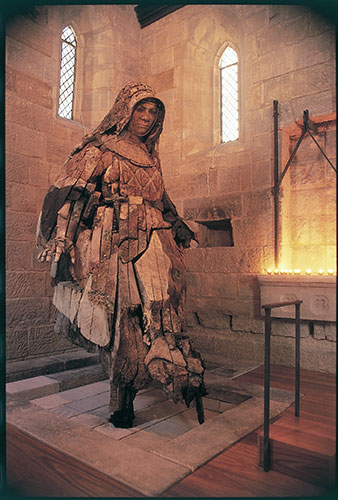

At the time of Mary MacKillop’s beatification in 1995, Archbishop Bathersby announced to the tumultuous applause of 6500 people that Brisbane’s original cathedral dating from 1850 would be restored as home for a diocesan shrine to our own Australian saint. The shrine would be in the apse and the nave would provide a small worship space for about ninety people. We turned again to John Elliott.

At the time of Mary MacKillop’s beatification in 1995, Archbishop Bathersby announced to the tumultuous applause of 6500 people that Brisbane’s original cathedral dating from 1850 would be restored as home for a diocesan shrine to our own Australian saint. The shrine would be in the apse and the nave would provide a small worship space for about ninety people. We turned again to John Elliott.

I had been involved with the Josephite sisters in an art competition at the time to try to develop an iconography for Mary that would move beyond the photographic images to something more penetrating and devotional. I was disappointed. So many of the portraits got stuck on the voluminous habit, with only the face of Mary to make a connection with the viewer. Our brief for the sculptor was to get beyond the surface and to lead people into the spirit of the blessed woman and to evoke a sense of awe.

The committee was frustrated because for the first few months we saw nothing but photocopies of a miscellaneous oriental deity. Elliott maintained that he was working hard. He said he was trying to determine if the figure should be larger or smaller than life, if it should be enclosed or open, if it should be raised or lowered. In due course, these studies produced fruit. Drawings, maquettes and meetings gave us a figure larger than life and set on stone slightly below the level of the timber floor.

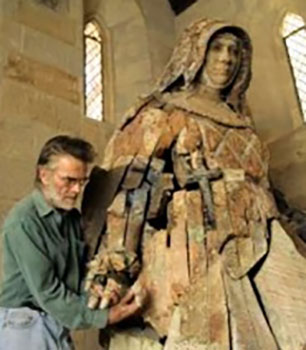

Poetically, he chose a huge hundred-year-old camphor laurel tree, a tree that would have been growing when Mary was alive. He sliced it up like an avocado and hollowed out the interior, heavy work for a man challenged by health issues. Then he painstakingly set about reorganising the surfaces until the figure of Mary MacKillop emerged. The tree recalled the simple slab huts in which she and her sisters taught and the landscape she traversed on horseback. The semi-abstract technique of leaving gaps enables the viewer to go beyond the exterior shape of the religious habit. What we encounter is a tough pioneering woman, striding forward with her sleeves pushed up, determined and confident in God’s providence, and yet, with her gaze modestly averted, a woman of compassion and interiority. Undoubtedly one of Australia’s most moving and adventurous images of Mary, our first saint.

Poetically, he chose a huge hundred-year-old camphor laurel tree, a tree that would have been growing when Mary was alive. He sliced it up like an avocado and hollowed out the interior, heavy work for a man challenged by health issues. Then he painstakingly set about reorganising the surfaces until the figure of Mary MacKillop emerged. The tree recalled the simple slab huts in which she and her sisters taught and the landscape she traversed on horseback. The semi-abstract technique of leaving gaps enables the viewer to go beyond the exterior shape of the religious habit. What we encounter is a tough pioneering woman, striding forward with her sleeves pushed up, determined and confident in God’s providence, and yet, with her gaze modestly averted, a woman of compassion and interiority. Undoubtedly one of Australia’s most moving and adventurous images of Mary, our first saint.

What is striking about these three outstanding works of liturgical art is how different each one is. That is because each is the result of the artist’s engagement with a different liturgical, theological and architectural brief. This is a sign of great creativity and insight.

Rev Dr Tom Elich, Director of Liturgy Brisbane, formed part of the reference group for each of these three sculptures.