DAPHNE MAYO caused a sensation in 1927 when she sculpted the tympanum of Brisbane’s City Hall. The conservative city fathers were astonished by the sight of this diminutive 32 year old woman wielding a jackhammer in the hot sun high above the streets. The work made her reputation and introduced the most productive decade of her life as a sculptor. Besides the women’s war memorial in Anzac Square and other commissions, she undertook a number of religious works which are an important part of the patrimony of the Australian Church.

She grew up in Brisbane and studied sculpture at the Brisbane Central Technical College. She won the Wattle Day Travelling Art Scholarship but her departure was delayed by the First World War. In 1920, she entered the sculpture school of the Royal Academy in London where she won the 1923 gold medal for sculpture and the Edward Stott Travelling Scholarship which enabled her to spend a further two years in France and Italy. She returned to live in Brisbane between 1925 and 1938. Then, after travelling for two years in Europe and north America, she spent twenty years in Sydney. She returned to Brisbane in 1960 and died in 1982. Small and frail, she was intensely self-disciplined and determined to succeed as a sculptor although such a physical art form was unusual for a woman of her time.

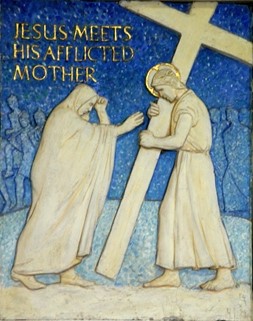

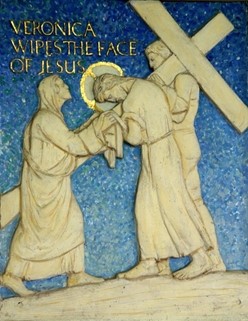

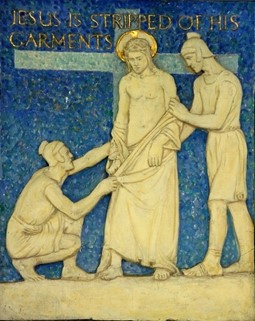

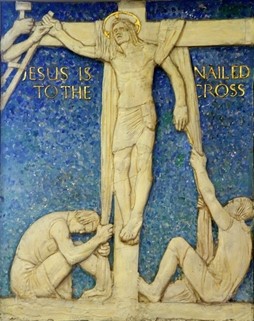

In 1930, she completed a set of Stations of the Cross in terracotta for Holy Spirit Catholic Church in New Farm, Brisbane. They are striking in their simplicity and strength of design. The principal figures are set against a strong blue background and highlighted with gold. Five years later she completed another set for All Saints Anglican Church in Brisbane. They have some similarities in composition but are much less effective because the principal figures meld into the crowd which surrounds them.

Jesus meets his afflicted mother

Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

Jesus stripped of His garments

Jesus is nailed to the cross

What did a woman’s sensibility bring to the story of Jesus’ passion and death? At once, the viewer notices the poetic gentleness of the portrayal. The soldiers and the crowd are not violent or rough with Jesus, even when they strip him and hoist him up to the cross. The figure of Jesus is serene and resigned, humble and obedient – quietly heroic without heroics. The images are designed to evoke tender devotion before a moving drama of love.

The encounter of Christ with Mary and Veronica is especially poignant. In neither case can Daphne Mayo bring herself to show Christ looking at the women. His head is bowed; they take the initiative. Mary reaches toward him in her grief, her cloak falling at the same angle as the cross, suggesting that in her sorrows, she too shares in the cross of Christ. Veronica’s determination as she steps forward is a beautiful contrast to the humbled Christ to whom she ministers.

Brisbane’s Archbishop, James Duhig, was a major patron of the arts. He commissioned Daphne Mayo not only to model the Stations of the Cross for the new Holy Spirit Church in New Farm, but also to carve the tympanum from Benedict stone.

Daphne’s travels had exposed her to the latest in artistic trends, but she was not impressed with the avant-garde. She became familiar with works by Maillol, Epstein and Hepworth which she found thought-provoking and exhilarating, though later in her life, she increasingly felt herself alienated from the modernist art scene represented by sculptors such as Tom Bass and Leonard Shillam. However she embraced the art deco style of which the Tympanum of Holy Spirit Church is an outstanding example. The Holy Spirit in the form of a dove is surrounded by tongues of flame representing the seven gifts of the Spirit. This is set in a geometric design like a sunburst which represents the radiating power of the Pentecost event. The twelve apostles, divided into four groups, kneel in adoration against a backdrop of cherubs. The house ‘where they were all gathered together in one place’ has been transformed into the heavenly court where the glory of divine power is made manifest.

At the church’s opening, Duhig commented on the uncommon but really beautiful front elevation. The beauty, of course, is enhanced by the use of Benedict Stone, the texture of which is admirable, and it is crowned by that fine sculptural group that fills the tympanum. I have rarely seen figures more exquisitely wrought and grouped, and I feel intensely proud that we have in Miss Daphne Mayo a young artist so gifted as to be able to give us work of such a high order.

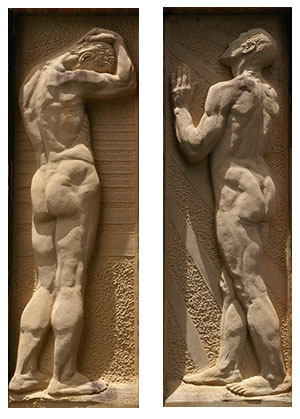

In 1934, Mayo completed several sandstone sculptures for the non-denominational chapel at Mt Thompson Crematorium in Brisbane. These monumental figurative works are rich with Christian symbolism. Flanking the main entrance to the chapel are two strong simple figures called Grief and Hope. They do more than represent personal emotions, drawing on the Easter symbol of light which evokes the resurrection. The sculptures could as easily be called Darkness and Light or Night and Day. Perhaps Daphne remembered her travels in Florence where she undoubtedly admired Michelangelo’s figures of Night and Day, Dawn and Dusk in the Medici Tomb at the basilica of San Lorenzo (and indeed, she was to be dubbed ‘Miss Michelangelo’ in 1941 by the ABC Weekly).

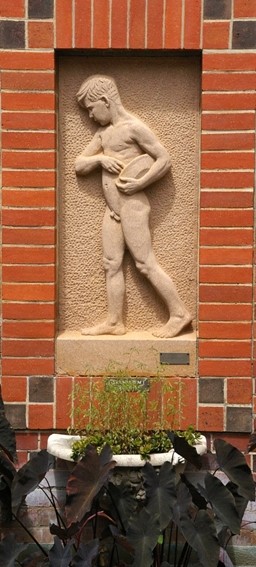

Located in an adjoining courtyard above a small pond, the figure of the boy ‘sowing the seed’ represents the Gospel parable of the sower from Mark 4:3-9. This is a story of the promise of God’s kingdom. Notwithstanding the setbacks represented by the bare path and its hungry birds, the shallow rocky soil and the withering sun, or the choking thorns, the sower achieves a good crop with a yield of thirty, sixty or even a hundredfold. It is a considerable achievement on the part of Mayo to create in these human figures universal symbols which rely on and draw from the history of Christian art. This body of work might lead us to reflect on what actually constitutes Christian art. Mayo’s creation of universal human symbols which are set against a background of Christian imagery is part of an answer.

Daphne Mayo also provided religious sculpture for St David’s Anglican Cathedral, Hobart. The connection was Richard Godfrey Rivers (1859-1925), her former art teacher in Brisbane. English-born Rivers, who came to Australia at the age of 30, was the art master at Brisbane Technical College for 25 years, president of the Queensland Art Society for much of that time, and one of the founders of the Queensland Art Gallery. He and his wife Selina moved to Hobart in 1915. After his death, his sister organised a memorial at the cathedral. Daphne made a bronze bas-relief of a saint with three birds, incorporating a birdbath in granite. It has been called a figure of St David, but it does not conform to the usual iconographic presentation of St David. More probably it is St Francis of Assisi who, according to legend, preached to the birds, a subject well-known from Giotto’s famous fresco.

Several years later in 1936, at the behest of the Dean, Daphne was commissioned to do two bronze saints for the cathedral tower which was then being completed. They depict St Anne with infant Mary and St Monica with child Augustine. They are powerful and original figures: St Anne holds the infant Mary (the mother of Jesus) and St Monica is shown with her son, the great St Augustine. The portrayal of St Anne with her infant is very unusual; she is traditionally shown teaching the child Mary to read. Here the sculpture evokes the image of the Madonna and Child Jesus, putting the viewer in mind of what the infant Mary will later become. St Monica is often shown praying and weeping for the conversion of her wayward adult son, Augustine. Here at a much earlier age, Augustine enjoys his mother’s protective hand on his shoulder and the guidance of her hand directing his attention heavenwards.

Both of these saintly married women are raised up as exemplary mothers and, indeed, the figures can be read as archetypes of Motherhood. Daphne Mayo has made a special contribution here to Christian iconography, for the choice and presentation of these feminine images are surely the product of a woman’s sensibility.

TOM ELICH